Evidence-Based Management of Nonspecific Low Back Pain in Adults

RELEASE DATE

March 1, 2021

EXPIRATION DATE

March 31, 2023

FACULTY

Mena Alrais Dellarocca, PharmD, RPh

Adjunct Instructor of Pharmacy Practice

University of Southern California School of Pharmacy

Los Angeles, California

FACULTY DISCLOSURE STATEMENTS

Dr. Dellarocca has no actual or potential conflict of interest in relation to this activity.

Postgraduate Healthcare Education, LLC does not view the existence of relationships as an implication of bias or that the value of the material is decreased. The content of the activity was planned to be balanced, objective, and scientifically rigorous. Occasionally, authors may express opinions that represent their own viewpoint. Conclusions drawn by participants should be derived from objective analysis of scientific data.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

Pharmacy

Pharmacy

Postgraduate Healthcare Education, LLC is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education as a provider of continuing pharmacy education.

UAN: 0430-0000-21-023-H01-P

Credits: 2.0 hours (0.20 ceu)

Type of Activity: Knowledge

TARGET AUDIENCE

This accredited activity is targeted to pharmacists. Estimated time to complete this activity is 120 minutes.

Exam processing and other inquiries to:

CE Customer Service: (800) 825-4696 or cecustomerservice@powerpak.com

DISCLAIMER:

Participants have an implied responsibility to use the newly acquired information to enhance patient outcomes and their own professional development. The information presented in this activity is not meant to serve as a guideline for patient management. Any procedures, medications, or other courses of diagnosis or treatment discussed or suggested in this activity should not be used by clinicians without evaluation of their patients’ conditions and possible contraindications or dangers in use, review of any applicable manufacturer’s product information, and comparison with recommendations of other authorities.

GOAL

To provide participants with an overview on the updated guidelines on the definition, evaluation, and treatment of adult patients with nonspecific low back pain, including the pharmacist’s role in educating and supporting these patients in their practice.

OBJECTIVES

After completing this activity, the participant should be able to:

- Identify committees that recently updated clinical practice guidelines for nonspecific low back pain in adults.

- Identify risk factors associated with nonspecific low back pain in adults.

- Define the difference between acute, subacute, and chronic nonspecific low back pain in adults.

- Describe the updated clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute, subacute, and chronic, nonspecific low back pain in adults.

ABSTRACT: To improve the knowledge base concerning the evaluation and treatment of nonspecific low back pain in adult patients, the Low Back Pain Work Group of the North American Spine Society’s Evidence-Based Guideline Development Committee and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and the U.S. Department of Defense both recently developed evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (CPG), which serve as an additional resource of updated evidence to the 2017 American College of Physicians CPG. These CPG have been created to aid practitioners in the evaluation and treatment of adult patients with nonspecific low back pain. Patients who have back pain often come into the pharmacy; therefore, community pharmacists should be aware of recent updated evidence in order to effectively counsel on both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic care.

It is estimated that up to 84% of all adults have low back pain (LBP) at some time in their lives, and it is one of the more common reasons for a primary care visit and job-related disability. Acute, or short-term, back pain lasts a few days to less than 4 weeks. Most LBP is acute. It tends to resolve on its own within a few days with self-care, and there is no residual loss of function. However, in some cases, it may take a few months for the symptoms to dissipate.

Chronic back pain is defined as pain that continues for 12 weeks or longer, even after an initial injury or underlying cause of acute LBP has been treated. About 20% of people affected by acute LBP go on to develop chronic LBP with persistent symptoms at 1 year. Even if pain persists, it does not always mean there is a medically serious underlying cause or one that can be easily identified and treated. In some cases, treatment successfully relieves chronic LBP, but in other cases pain continues despite medical and surgical treatment. To improve the knowledge base concerning the evaluation and treatment of nonspecific LBP in adult patients, pharmacists should be aware of both the 2020 LBP North American Spine Society (NASS) Evidence-Based Guideline Development Committee and 2019 Veteran’s Administration/U.S. Department of Defense (VA/DoD) clinical practice guideline (CPG) recommendations for treatment, which can add and serve as an update to the previously published 2017 American College of Physicians (ACP) CPG.1-3

EPIDEMIOLOGY

In 2010, back symptoms were the principal reason for 1.3% of office visits in the United States. Spinal disorders accounted for 3.1% of diagnoses in outpatient clinics. The prevalence of back pain has been estimated with surveys. A 2012 systematic review estimated that the global point prevalence of activitylimiting LBP lasting for more than 1 day was 12%, and the one-month prevalence was 23%. Other survey estimates of the prevalence of LBP have ranged from 22% to 48%, depending on the population and definition.4-6

RISK FACTORS

Risk factors associated with LBP complaints include smoking, obesity, age, female gender, physically strenuous work, sedentary work, psychologically strenuous work, low educational attainment, Workers’ Compensation insurance, job dissatisfaction, and psychologic factors such as anxiety and depression.5-7

ETIOLOGIES

Although there are many etiologies of LBP, the majority of patients seen in a community pharmacy setting will have nonspecific LBP. This is where the patient will present with LBP in the absence of a specific underlying condition that can be reliably identified either from patient or medical history. Many of these patients may have musculoskeletal pain, and most improve within a few weeks.

OVERALL MANAGEMENT OF CARE FOR ACUTE LBP

The goal of care for patients with acute LBP is short-term symptomatic relief since most will improve within 4 weeks. Pharmacists can advise nonpharmacologic treatment with superficial heat. The recent 2020 NASS CPG suggest that the use of heat for acute LBP results in short-term improvements in pain. For patients who have tried and are looking for other options, making a referral for getting a massage, acupuncture, and spinal manipulation are other reasonable recommendations.

Pharmacists can share that evidence is uncertain with no superiority of one modality over another, and this will ultimately depend upon patient preference as well as treatment cost and accessibility. Generally, for patients who prefer pharmacotherapy or in whom nonpharmacologic approaches are inadequate, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) with or without a nonbenzodiazepine skeletal muscle relaxant may be used for pharmacologic therapy. This is recommended by both VA/DoD and NASS CPG. Furthermore, pharmacists should not advise bed rest for patients with acute LBP. This is because patients who are treated with bed rest have more pain and slower recovery than ambulatory patients. Activity modification should generally be minimal, with patients returning to activities of daily living and work as soon as possible. If activity is painful or increases pain, patients can be advised to do as much as they can and as tolerated and to follow-up with their physician.

Nonpharmacologic Management for Acute LBP

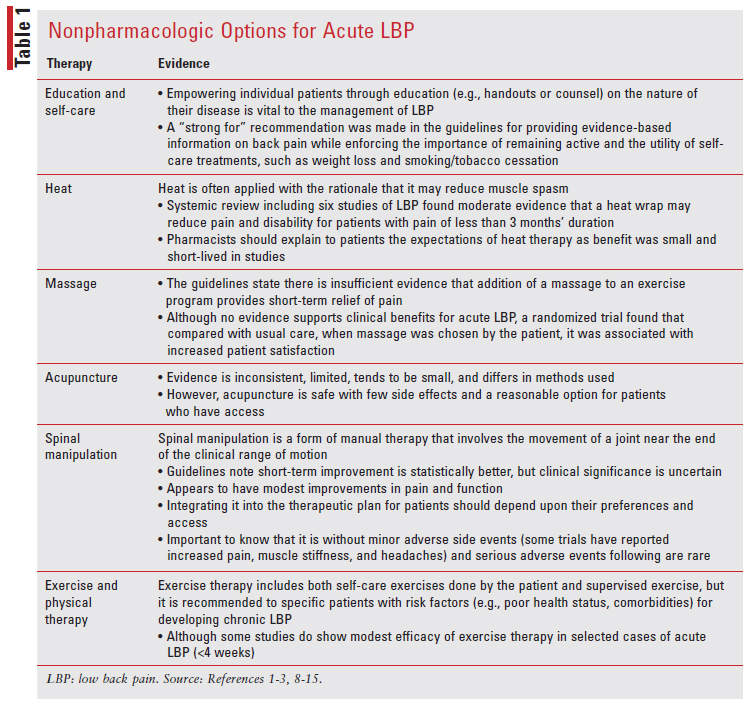

Pharmacists should be aware that the effectiveness of nonpharmacologic therapies is generally of low to moderate quality based on the evidence (TABLE 1). The choice among these options really depends upon patient preference and their cost and accessibility.

Pharmacologic Management for Acute LBP

Initial therapy: If pharmacotherapy is used, pharmacists should be aware that CPG recommend a trial of short-term (e.g., 2-4 weeks) treatment of an NSAID.

NSAIDs: Both of the updated CPGs suggest NSAIDs for the treatment of LBP, and there is fair evidence to suggest this. NSAIDs can be recommended to those patients with acute LBP who do not have contraindications to treatment. Many NSAID options exist with no clear difference in pain relief among them. Ibuprofen (400-600 mg four times daily) or naproxen (250-500 mg twice daily) often may be prescribed. NSAIDs provide modest symptomatic relief for acute LBP. In a 2008 systematic review and meta-analysis of 11 randomized trials, global symptomatic improvement after 1 week was modestly greater for patients with acute LBP treated with NSAIDs compared with placebo (risk ratio 1.19; 95% CI, 1.07-1.35). However, NSAIDs were associated with more side effects compared with either placebo or acetaminophen, and this emphasizes the importance of counseling patients on decreasing the dose as tolerated. Pharmacists could recommend and work with the provider to utilize COX-2–selective NSAIDs over nonselective NSAIDs based on patient risk factors as they have shown statistically fewer adverse effects. NSAIDs may have significant renal, gastrointestinal, and cardiovascular adverse effects and may be contraindicated in some patients. It is important to be mindful of your older patients as NSAID toxicities are more commonly seen.1,2

Acetaminophen: Acetaminophen has historically been considered an option for first-line therapy for LBP. However, evidence of efficacy has been mixed, and a 2016 Cochrane review concluded that there was high-quality evidence that acetaminophen showed no benefit compared with placebo in acute LBP. There is also evidence that the addition of acetaminophen to short-term NSAID therapy provides no further benefit. Given that acetaminophen has clear risks and questionable benefit, recent CPG do not recommend it as either initial or supplemental therapy for the majority of patients with acute LBP. The VA/DoD did recommend a “strong against” recommendation for chronic use of oral acetaminophen, whereas the ACP guidelines do not provide clear recommendations. However, in selected patients for whom there are no safe alternatives and acetaminophen is the least potentially harmful treatment, it is reasonable to consider a trial of acetaminophen as an initial therapy. Acetaminophen 650 mg orally every 6 hours as needed (maximum 3 grams per 24 hours) for most adults is reasonable, although pharmacists should keep in mind the lower total daily limit for older adult patients, those with any hepatic impairment, those taking multiple medications, and patients with other factors that predispose them to hepatotoxicity (e.g., alcohol abuse).1-3

Second-Line Therapy: For patients with pain refractory to initial pharmacotherapy, the addition of a nonbenzodiazepine muscle relaxant can be recommended, although the evidence is moderate in acute LBP. In patients who cannot tolerate or have contraindications to muscle relaxants, combining NSAIDs and acetaminophen is another option; however, pharmacists should be aware that there are little data to support the use of this combination.1-3

Nonbenzodiazepine Skeletal Muscle Relaxants: These are a diverse group of drugs with similar physiologic effects, including analgesia and a degree of skeletal muscle relaxation or relief of muscle spasm. They include a variety of structurally unrelated compounds that can be classified into two main categories: antispastic and antispasmodic medications. These agents have different indications, mechanisms of action, and safety profiles. Understanding these differences can improve selection of an appropriate agent to optimize patient-centered therapy. The agents commonly used for LBP include cyclobenzaprine, methocarbamol, carisoprodol, baclofen, chlorzoxazone, metaxalone, orphenadrine, and tizanidine.

Pharmacists should be aware that benzodiazepines are not used because they are not effective in improving pain or functional outcome and there is potential for abuse. Patients who can tolerate the potential sedating effects of these medications may benefit from the addition of a nonbenzodiazepine muscle relaxant to initial pharmacotherapy with NSAIDs or acetaminophen. These are not to be recommended as initial therapy, as they tend to have sedating side effects that limit patients’ ability to conduct activities of daily living. Risks of these agents increase with age, and these agents should be used with caution in older adults. These agents are poorly tolerated in patients older than age 65 years due to anticholinergic adverse events, sedation, and risk for falls and fractures. For patients who cannot tolerate the sedating effects of muscle relaxants during the daytime, NSAIDs or acetaminophen during the day with muscle relaxants before bedtime may be helpful.1

Opioids: If opioids are used for acute LBP, the duration of therapy should be brief. The 2016 CDC recommendation is to limit the duration of opioid therapy for acute pain to less than 3 days for most patients unless circumstances clearly warrant additional therapy. Even in those cases, more than 7 days is rarely needed. There are few data on the efficacy and safety of opioids for acute LBP. Most studies of opioids focus on chronic LBP and are not generalizable to acute LBP. Working with the physician and patient, pharmacists can recommend to limit opioids to bedtime use to facilitate sleep and reduce the chances of developing dependence or tolerance.16

Adverse effects of opioids include sedation, confusion, nausea, and constipation. Respiratory depression is an issue at higher doses, but rarely at the doses used for acute LBP. As with all medications, older patients are more susceptible to side effects. Patients given combination drugs containing acetaminophen or NSAIDs should be advised not to use them concurrently with OTC analgesics without carefully reviewing the contents with a pharmacist. It is well known that misuse is a concern with opioids, but it is also important to note that addiction and abuse are rare with short-term prescription for acute pain and more commonly seen in patients using opioids for the treatment of chronic LBP.

Overall Management of Care for Subacute and Chronic LBP

Subacute LBP is pain lasting anywhere between 4 to 12 weeks, whereas chronic LBP is pain lasting longer than 12 weeks.

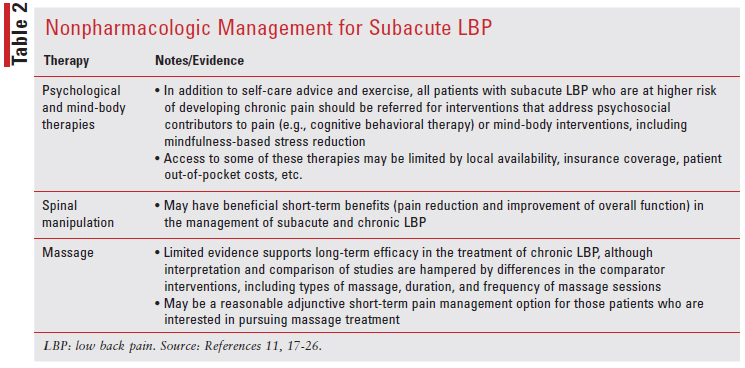

Subacute LBP Management: For some patients, an episode of LBP may last beyond 4 weeks. The period from 4 to 12 weeks represents a transition period in which improvement in pain and function typically is less rapid than in the acute phase, and some patients may develop chronic pain. In this period of subacute LBP, the goals of treatment are to work towards resolution of symptoms, aim to identify those at higher risk for developing chronic pain, and to intervene as early as possible in such patients (TABLE 2). For those patients whose symptoms persist beyond 3 months, the goal of treatment moves to controlling pain, maintaining activities of daily living function, and preventing disability.

Pharmacologic Treatment for Subacute LBP

In patients with subacute LBP with more severe pain symptoms, pharmacologic therapy for additional symptom management is appropriate. Although nonpharmacologic therapy is generally preferred over pharmacologic therapy, they are commonly used together in clinical practice. The goal of medications is to provide symptomatic relief of pain symptoms while allowing the patient to participate in active therapies, including exercise, psychological, and/or mind-body interventions. A short course of medication for adjunctive symptom management is recommended, as the data only support evidence of benefit in short-term use.27,29

NSAIDs: For patients with subacute LBP, NSAIDs are recommended as first-line therapy. Options could include ibuprofen 400 mg to 800 mg orally every 8 hours as needed or naproxen 250 mg to 500 mg orally every 12 hours, as needed.

Patients should be encouraged to take the lowest effective dose of an NSAID for the shortest period of time. High-quality data are limited on optimal NSAID dosing strategies for the management of subacute LBP, but one reasonable approach is to have the patient take a standing dose for 1 to 2 weeks, then decrease the dose and dosing frequency as tolerated. Systematic reviews of randomized trials found that compared with placebo, NSAIDs are slightly more effective for both pain relief and improvement in function in mixed back pain (acute and chronic) populations. Evidence for the efficacy of NSAIDs in the management of subacute LBP is sparse, but the benefits likely extend to those with subacute symptoms.27,29

Patients With Contraindications to NSAIDs: For patients who are unable to take NSAIDs (i.e., due to allergy or other intolerance, chronic kidney disease, hypertension, peptic ulcer disease, or cardiovascular disease), acetaminophen is a reasonable alternative at 650 mg orally every 6 hours as needed (maximum 3 grams per 24 hours) for most adults. Evidence supporting the use of acetaminophen for chronic LBP is mostly indirect. In systematic reviews of patients with multisite osteoarthritis (not limited to the back), acetaminophen was more effective than placebo but was consistently inferior to NSAIDs for pain relief. Pharmacists should keep in mind the total daily dose for elderly patients and those with any hepatic impairment, as well as alcohol use. Acetaminophen overdose can lead to severe hepatotoxicity and is the most common cause of acute liver failure in the U.S. Other possible adverse effects that have been associated with acetaminophen include chronic kidney disease, hypertension, and peptic ulcer disease. Patients should be made aware of the safe total daily dose of acetaminophen and to consider all sources of acetaminophen in both prescription and OTC medications.27,29

Nonbenzodiazepine Skeletal Muscle Relaxant: This may be used as a second line of treatment if the NSAID or acetaminophen therapy is inadequate. This is to be recommended as needed, for symptoms not well managed with NSAIDs or acetaminophen alone. Options could include cyclobenzaprine 5 mg to 10 mg orally three times daily as needed (with one of the doses taken at bedtime to help with sleep) or tizanidine 4 mg to 8 mg orally three times daily as needed.

When a skeletal muscle relaxant is needed, ensuring the lowest effective dose and dosing frequency is advised. A patient may start with a standing dose for the first 1 to 2 weeks of treatment and then decrease the dose and dosing frequency as tolerated. Patients who may be more sensitive to the sedating effects (e.g., elderly, patients with organ impairment, and those receiving potentially interacting medications) may better tolerate a reduced starting dose, less frequent administration, and a more gradual titration. Regardless, pharmacists should counsel patients of their potential to cause drowsiness. High-quality data on the use of skeletal muscle relaxants in patients with subacute LBP are lacking, and the recommendation to use them in this patient population is based upon the efficacy of these medications in patients with acute LBP. In a systematic review, skeletal muscle relaxants were better than placebo for short-term improvement in pain in patients with acute LBP, but there was insufficient evidence to determine whether they were effective for subacute or chronic LBP.29,30

Overall Chronic LBP Management: All patients with chronic LBP (pain that persists beyond 12 weeks) should receive self-care advice and participate in exercise or movement-based therapy.

Nonpharmacologic Management for Chronic LBP

Many patients with chronic LBP may not have disabling symptoms or significant functional impairment. For these patients, pharmacists may educate and counsel them on the importance of a regular exercise program. Patients who are motivated will likely do well with an independent exercise program, while others may benefit from participation in a more structured or clinician-supervised program. For patients with a history of recurrent LBP, participation in a regular exercise therapy program may help prevent future exacerbations of LBP.1-3,17

Those patients with chronic LBP and more severe, persistent, disabling symptoms and significant functional impairment will require more intensive management strategies. For such patients, the goal of care is to manage pain, increase function, and maximize coping skills.

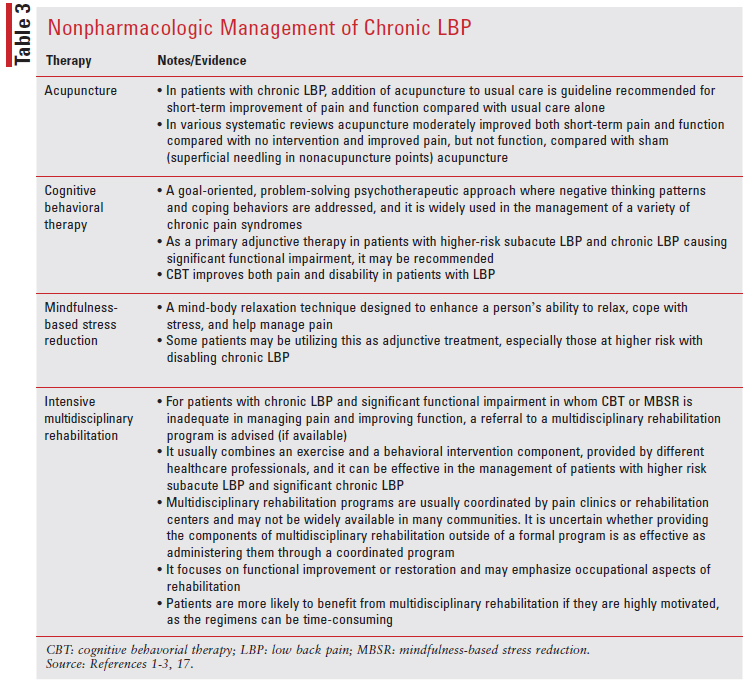

Utilizing a combination of exercise therapies, psychological and/or mind-body interventions, pharmacologic therapy, and other treatments is often required to achieve this goal. Such patients may benefit from participation in a clinician-supervised exercise program as it may provide structure and reassurance and ultimately allow the patient to progress to performing more independent exercise. Maintaining an emphasis on active therapy is consistent with a biopsychosocial approach to pain, which engages patients in their care, more directly aiming to improve function and not just reducing pain. Movement-based interventions with a mind-body component, including tai chi and yoga, are particularly well suited for patients with LBP and functional limitations. Exercise and movement-based therapies can be combined with cognitive beharioral therapy and mindul-based stress therapy (TABLE 3).1-3,17

Pharmacologic Management for Chronic LBP

Although nonpharmacologic therapy is preferred over pharmacologic therapy for the management of chronic LBP, they are commonly used together in clinical practice. The goal of medications is to provide symptomatic relief of pain while allowing the patient to participate in active therapies (exercise and/or psychological treatments), encouraging increased function and improved coping. In patients with persistent, disabling chronic LBP and functional impairment, pharmacologic therapy as adjunctive treatment concurrently with exercise and psychological therapies or mind-body interventions can be beneficial. For patients with significant chronic LBP who need adjunctive medication for symptom management, the supporting data on the duration of medication treatment are limited. Thus, limiting the duration of use for most medications is ideal but not always possible.

First-Line Pharmacologic Therapy for Chronic LBP

NSAIDs: The majority of patients with chronic LBP will have already tried NSAID treatment (either of their own initiative or upon prior physician prescription) during the acute or subacute phase. In these patients, if NSAIDs are effective in controlling symptoms, pharmacists can recommend continuing them without adding additional pharmacologic therapy. They should remember to counsel patients on utilizing the lowest effective dose and frequency, favoring an “as needed” dosing schedule, and working with the provider to attempt to taper and ultimately discontinue these drugs if possible. NSAIDs are associated with side effects (e.g., gastrointestinal, renal, and cardiovascular), and pharmacists should continue to assess patients’ risk factors for complications before continuation or dispensing prescription.1-3,17

If NSAIDs are only partially effective in controlling symptoms and additional pain control is required, patients may continue NSAIDs, but adding a second-line pharmacologic therapy is recommended. It is not recommended to use NSAIDs for chronic therapy if they were ineffective in managing subacute LBP symptoms.

For patients who are unable to take NSAIDs (e.g., due to allergy or other intolerance, chronic kidney disease, hypertension, peptic ulcer disease, or cardiovascular disease), acetaminophen is a reasonable alternative.1-3,17

Second-Line Pharmacologic Therapy for Chronic LBP

For patients with chronic LBP in whom NSAID therapy is ineffective or inadequate and who require long-term pharmacologic therapy, duloxetine and tramadol are commonly used. Duloxetine, a selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), is preferred over tramadol, a drug with mixed opiate agonist and SNRI activity and that carries the potential for misuse and dependency. Another less preferred alternative may be tricyclic antidepressants, especially for those patients with pain symptoms that interfere with sleep or for those in whom duloxetine is ineffective or cost-prohibitive, but pharmacists should be aware the role of these are uncertain in the treatment of chronic pain.1-3,17

Duloxetine: Duloxetine is usually started at 30 mg orally once daily, and after 1 week it is increased to 60 mg orally once daily, if tolerated. It needs to be taken every day, not on an as-needed basis. Three randomized trials found duloxetine more effective than placebo for LBP. However, all trials were sponsored by the drug manufacturer, differences were small, and patients were more likely to discontinue duloxetine compared with placebo due to adverse effects. Duloxetine was approved by the FDA in 2012 for treatment of chronic musculoskeletal pain, including LBP. Duloxetine is preferred over tramadol in patients for whom there is a concern over the possibility of drug abuse or misuse. Depression is common in patients with chronic LBP, and as an antidepressant, duloxetine may have an additional indication for use in a patient with chronic LBP and coexisting depression. However, the analgesic effects of duloxetine are independent of whether or not depression is present.1-3,17

Tramadol: An opioid agonist that also blocks reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine, tramadol should be used similarly to opioids, limiting regular use to a few days and total use up to 2 weeks. Tramadol may have a lower risk of constipation and dependence than traditional opioids, but it carries the risk of serotonin syndrome, especially when combined with other serotonergic agents. It can also lower the seizure threshold. This agent may be taken either as a standing dose or on an as-needed basis. For instance, when therapy is initiated, it may be prescribed as taken as-needed, and the dosing schedule subsequently adjusted according to the patient’s response. It is typically started at the lowest dose, particularly in older adults and opioid-naïve patients (e.g., tramadol 25-50 mg orally every 6 or 8 hours, as needed), then increase the dose if necessary (e.g., tramadol 50-100 mg orally every 6 hours, as needed). If a patient has constant symptoms, however, it can be prescribed to be taken on a standing schedule (e.g., tramadol 50 mg orally every 6 hours); the frequency is then decreased or changed to an as-needed dosing schedule as symptoms improve. It is not recommended to use a long-acting tramadol preparation when initiating tramadol therapy because it complicates dose titration. In patients already on a stable, standing dosing schedule, a long-acting tramadol preparation may be more convenient, but it is generally more expensive and not associated with improved pain relief or function.31,32

Topical and Herbal Agents: Repeated applications of capsaicin may bring a long-lasting desensitization to pain (increase of pain threshold) that is fully reversible. Studies have shown improvement in pain scores after 3 weeks of treatment. The recent guidelines recommend topical capsicum as an effective treatment for LBP on a short-term basis (3 months or less). However, they found insufficient evidence to support the use of lidocaine patches in this setting.2

Opioids: These medications should not be used routinely for the management of chronic LBP given poor or modest efficacy and the potential for harm. Opioid use should be restricted to patients not highly vulnerable to drug dependence, misuse, or addiction and only when the potential benefits outweigh the risks; in addition, the lowest possible dose should be used, and use should be monitored closely. The VA/DoD CPG have diverged from other clinical guidelines regarding several pharmacologic treatment options, particularly the use of benzodiazepines, steroid medications, opioid medications, and acetaminophen. The 2017 ACP guidelines provide a weak recommendation to “consider opioids as an option in patients who have failed” other treatments, whereas the VA/ DoD CPG have made a “strong against” recommendation for initiating long-term opioid therapy and that “any opioid therapy should be kept to the shortest duration and lowest dose possible.”1-3

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of opioid use in patients with chronic LBP identified few highquality and no long-term trials. In the available trials, opioids produced only small, short-term improvements in pain and function when compared with placebo and had no benefit compared with NSAIDs or antidepressants. A long-term, randomized trial compared opioids versus nonopioid medications in 240 VA patients with moderate-to-severe chronic back pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis. At 1 year, there was no difference in pain-related function, while pain intensity was slightly better in nonopioid-treated patients. In addition, patients treated with opioids experienced more negative side effects. Studies of the use of opioids for chronic and subacute LBP rarely quantify the risk of important harms, such as abuse or addiction, and have typically excluded patients at higher risk for these types of adverse events. Opioids are frequently prescribed for chronic LBP, which is inconsistent with evidence-based care and guideline recommendations.1-3,33

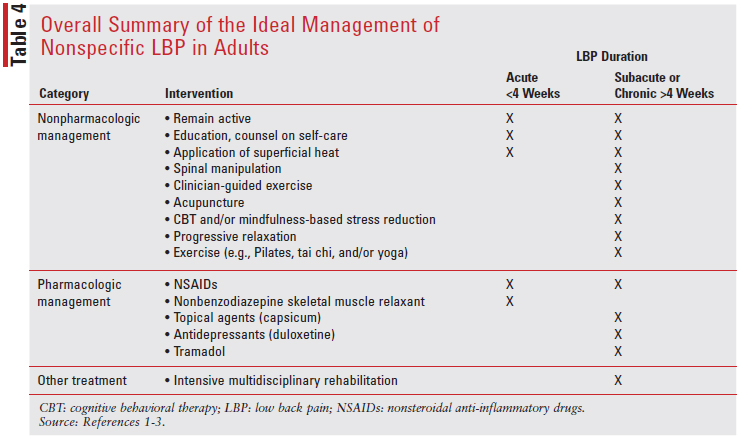

As an overview and summary of the ideal management of nonspecific LBP in adults, these evidence based CPG have been created and updated using techniques of evidence-based medicine to aid practitioners in the treatment of adult patients with nonspecific LBP (TABLE 4).

CONCLUSION

In appreciation of the newer evidence regarding effective nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic management of LBP, community pharmacists have the opportunity to effectively engage with both patients and physicians and assess which management of pain symptoms are attuned to the latest clinical evidence and guidelines. It is important for pharmacists to interview patients and correctly identify the category of LBP the patient falls under, as both the CPG treatment approach and recommendations will differ based on this. The position of a community pharmacist is pivotal in LBP assessment and management, from both a pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic standpoint.

REFERENCES

1. Pangarkar SS, Kang DG, Sandbrink F, et al. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline: diagnosis and treatment of LBP. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(11):2620-2629.

2. Kreiner SD, et al. Guideline summary review: an evidence-based clinical guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. Spine. 2020;998-1024.

3. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, et al. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:514-530.

4. Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Martin BI. Back pain prevalence and visit rates: estimates from U.S. national surveys, 2002. Spine. 2006;31:2724.

5. Skovron ML, Szpalski M, Nordin M, et al. Sociocultural factors and back pain. A population-based study in Belgian adults. Spine. 1994;19:129.

6. Papageorgiou AC, Croft PR, Ferry S, et al. Estimating the prevalence of low back pain in the general population. Evidence from the South Manchester Back Pain Survey. Spine. 1995;20:1889-1894.

7. Katz JN. Lumbar disc disorders and low-back pain: socioeconomic factors and consequences. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;(88 suppl2)2:21-24.

8. French SD, Cameron M, Walker BF, et al. Superficial heat or cold for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD004750.

9. Furlan AD, Giraldo M, Baskwill A, et al. Massage for low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015; CD001929.

10. Eisenberg DM, Post DE, Davis RB, et al. Addition of choice of complementary therapies to usual care for acute low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Spine. 2007;32:151.

11. Liu L, Skinner M, McDonough S, et al. Acupuncture for low back pain: an overview of systematic reviews. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015:328196.

12. Paige NM, Miake-Lye IM, Booth MS, et al. Association of spinal manipulative therapy with clinical benefit and harm for acute low back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2017;317:1451-1460.

13. van Tulder MW, Malmivaara A, Esmail R, Koes BW. Exercise therapy for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD000335.

14. Brennan GP, Fritz JM, Hunter SJ, et al. Identifying subgroups of patients with acute/subacute “nonspecific” low back pain: results of a randomized clinical trial. Spine. 2006;31:623-631.

15. Fritz JM, Delitto A, Erhard RE. Comparison of classification-based physical therapy with therapy based on clinical practice guidelines for patients with acute low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. Spine. 2003;28:1363-1371.

16. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-49.

17. Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al. Nonpharmacologic therapies for low back pain: a systematic review for an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:493-505.

18. Rubinstein SM, van Middelkoop M, Assendelft WJ, et al. Spinal manipulative therapy for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(2):CD008112.

19. Walker BF, Hebert JJ, Stomski NJ, et al. Short-term usual chiropractic care for spinal pain: a randomized controlled trial. Spine. 2013;38:2071.

20. Bronfort G, Hondras MA, Schulz CA, et al. Spinal manipulation and home exercise with advice for subacute and chronic back-related leg pain: a trial with adaptive allocation. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:381-391.

21. Schneider M, Haas M, Glick R, et al. Comparison of spinal manipulation methods and usual medical care for acute and subacute low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. Spine. 2015;40:209-217.

22. Brinkhaus B, Witt CM, Jena S, et al. Acupuncture in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:450.

23. Haake M, Muller HH, Schade-Brittinger C, et al. German Acupuncture Trials (GERAC) for chronic low back pain: randomized, multicenter, blinded, parallel-group trial with 3 groups. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1892-1898.

24. Furlan AD, van Tulder MW, Cherkin DC, et al. Acupuncture and dry-needling for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(1):CD001351.

25. Manheimer E, White A, Berman B, et al. Meta-analysis: acupuncture for low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:651-663.

26. Lam M, Galvin R, Curry P. Effectiveness of acupuncture for nonspecific chronic low back pain: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Spine. 2013;38:2124-21238.

27. Enthoven WT, Roelofs PD, Deyo RA, et al. Non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs for chronic low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD012087.

28. Kearney PM, Baigent C, Godwin J, et al. Do selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors and traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs increase the risk of atherothrombosis? Meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ. 2006;332:1302-1308.

29. Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al. Systemic pharmacologic therapies for low back pain: a systematic review for an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:480-492.

30. van Tulder MW, Touray T, Furlan AD, et al. Muscle relaxants for nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the cochrane collaboration. Spine. 2003;28:1978-1992.

31. Peloso PM, Fortin L, Beaulieu A, et al. Analgesic efficacy and safety of tramadol/acetaminophen combination tablets (Ultracet) in treatment of chronic low back pain: a multicenter, outpatient, randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2004;31 (12):2454-2463.

32. Ruoff GE, Rosenthal N, Jordan D, et al. Tramadol/acetaminophen combination tablets for the treatment of chronic lower back pain: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled outpatient study. Clin Ther. 2003;25(4):1123-1141.

33. Krebs EE, Gravely A, Nugent S, et al. Effect of opioid vs nonopioid medications on pain-related function in patients with chronic back pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis pain: the SPACE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2018;319:872-882.