Managing Chronic, Noncancer Pain With Opioids

RELEASE DATE

March 1, 2022

EXPIRATION DATE

March 31, 2024

FACULTY

Vorlak Hong, PharmD

Clinical Pharmacy Specialist

Spectrum Health

Grand Rapids, Michigan

Jennifer LaPreze, PharmD, BCACP, CDCES, CPP

Clinical Pharmacist

Atrium Health

Fort Mill, South Carolina

FACULTY DISCLOSURE STATEMENTS

Drs. Hong and LaPreze have no actual or potential conflicts of interest in relation to this activity.

Postgraduate Healthcare Education, LLC does not view the existence of relationships as an implication of bias or that the value of the material is decreased. The content of the activity was planned to be balanced, objective, and scientifically rigorous. Occasionally, authors may express opinions that represent their own viewpoint. Conclusions drawn by participants should be derived from objective analysis of scientific data.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

Pharmacy

Pharmacy

Postgraduate Healthcare Education, LLC is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education as a provider of continuing pharmacy education.

UAN: 0430-0000-22-025-H08-P

Credits: 2.0 hours (0.20 ceu)

Type of Activity: Knowledge

TARGET AUDIENCE

This accredited activity is targeted to pharmacists. Estimated time to complete this activity is 120 minutes.

Exam processing and other inquiries to:

CE Customer Service: (800) 825-4696 or cecustomerservice@powerpak.com

DISCLAIMER

Participants have an implied responsibility to use the newly acquired information to enhance patient outcomes and their own professional development. The information presented in this activity is not meant to serve as a guideline for patient management. Any procedures, medications, or other courses of diagnosis or treatment discussed or suggested in this activity should not be used by clinicians without evaluation of their patients’ conditions and possible contraindications or dangers in use, review of any applicable manufacturer’s product information, and comparison with recommendations of other authorities.

GOAL

To educate pharmacists about the management of noncancer pain.

OBJECTIVES

After completing this activity, the participant should be able to:

- Review guidelines regarding prescribing opioids for noncancer pain.

- Describe current recommendations for tapering noncancer pain opioid management.

- Describe effective communication strategies to discuss the benefits and harms of opioids with patients.

- Discuss the impact of COVID-19 on the opioid epidemic.

ABSTRACT: In recent years, there have been recommendations to decrease prescribing of opioids for noncancer pain. Chronic pain should primarily be managed by nonpharmacologic or nonopioid pharmacologic therapy. A thorough medical history and proper diagnosis assist with appropriate management. When using opioids for pain management, the lowest effective dosage and shortest duration should be utilized. If tapering opioids is appropriate, the provider needs to utilize effective communication strategies, follow-up frequently, and utilize validated assessment tools to help reduce withdrawal symptoms. Telemedicine can be employed during the COVID-19 pandemic to ensure continued medication access and to provide regular follow-up.

In 2012, 259 million prescriptions for opioid pain medications were written.1 It is estimated that 20% of patients with noncancer pain receive an opioid prescription.1 Approximately 10.1 million people misused prescription opioids in 2020, and 1.6 million people had an opioid use disorder in the past year.2 In 2017, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) declared a public health emergency and released a five-point opioid strategy as described in TABLE 1 to combat the opioid epidemic.2,3

With the current opioid epidemic, there are questions regarding what is considered a safe dose of opioids, the role of opioids in chronic pain management, and the risk of overdose or abuse. Multiple guidelines have recommended that opioid prescriptions for noncancer pain not exceed 50 morphine equivalents due to the risk associated with abuse.1,4,5 This article will discuss validated tools that clinicians can use to help assess a patient’s pain and, if appropriate, determine a plan to taper the opioid.

Effective treatment for pain starts with an accurate diagnosis. Pain is usually described as either nociceptive or neuropathic; however, symptoms may overlap and may not be easily categorized. A thorough history and physical examination should occur. A pharmacist can help gather a detailed medication history from the patient. This should include medications currently being used, past medications, samples, supplements, and any other OTC medications. During this discussion, the pharmacist can also inquire about substance abuse.30 Having the right diagnosis and medication history will help the provider make a more informed decision on treatment options.

Chronic pain is most commonly defined as pain that lasts longer than 3 months or past the time of normal healing.1 The focus on treatment should shift from completely eliminating pain to minimizing the impact of pain on quality of life.6

In 2016, A Compact to Fight Opioid Addiction focused on reducing inappropriate prescribing of opioids, and many states have enacted opioid-limiting legislation.7

Given that pain is multifactorial, nonpharmacologic therapies for pain include cognitive behavioral therapy, such as mindfulness or relaxation techniques and physical therapy. If pharmacologic therapy is appropriate, TABLE 2 shows some nonopioid pharmacologic therapy options for some causes of pain. For instance, acetaminophen is first-line therapy for osteoarthritis.1 Neuropathic pain firstand secondline medications include anticonvulsants, tricyclic antidepressants, and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).1 Patients with chronic pain may have depression, which can exacerbate pain and worsen physical symptoms; pain may also benefit from antidepressant medication use.1 If opioid therapy is warranted, it is recommended to combine it with nonpharmacologic therapy and nonopioid pharmacologic therapy and the lowest necessary dose for the shortest duration.1,4 Immediate-release opioids are preferred over extended-release/long-acting formulations.1

Clinicians should discuss appropriate treatment regimens with patients and set realistic goals for pain function at each visit. There are assessment tools that are useful for assessing daily function and pain, potential risk of addiction before starting opioids, or abuse potential while on long-term opioids (TABLE 3). The validated assessment tools in TABLE 3 are not all inclusive, and more tools are available that can be utilized in practice.4 It is recommended that this process, which sets standards for opioid prescribing, should be the same for all patients, regardless of abuse history.8 The provider should be aware of legal requirements that are necessary to satify prior to prescribing opioids. An example would be the state of Michigan, where providers are required to have a conversation with the patient about risks versus benefits of opioids prior to prescribing them to establish a patientprovider relationship. Part of this process includes the review of the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) to assess history of opioid use and urine drug-screen monitoring. Community pharmacists can help in the monitoring process by checking in with the patient when dispensing opioids and with monitoring (adhering to the PDMP). Pharmacists can notify prescribing providers if there is a question of abuse or drug interactions.30

Tools that can be used to determine if the opioid is improving function and pain are the Pain, Enjoyment of Life and General Activity (PEG) scale and the Two-Item Graded Chronic Pain Scale.4 Both scales help assess a patient’s pain and functionality and should be assessed at each visit.

The PEG was developed based on the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) scale to make it easier to use in the primary care setting. The BPI scale for assessing pain intensity/functional impairment and pain-related interference in daily activity and the healthcare familiarity with a 0 to 10 scale were used to create the PEG.9 The PEG is comparable to the BPI in assessing patients’ pain, and the resulting three-question PEG tool allows clinicians to quickly assess function and pain while checking for other conditions.9

The Two-Item Graded Chronic Pain Scale was created from a longer graded chronic scale. The original scale was a six-item question that asked patients about their pain and interference in activity for multiple time periods, which made scoring complicated and more time-consuming. It was simplified to just two questions to help determine pain intensity and interference, proving to be an effective tool during a primary care visit.10

Clinicians should not continue to prescribe opioids if there is not a clinically meaningful improvement in function or pain interference during the acute pain phase.1,4 Each state has its own PDMP, which should be checked to verify that a patient’s controlled substance history is consistent with prescribing.1 Two tools that can be used to assess for abuse potential are the Opioid Risk Tool (ORT) and the Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain (SOAPP-R). The ORT is a five-item clinician self-administered tool that can be used to help predict abuse-related behaviors in patients with chronic pain.4 It focuses on family/personal history of substance/alcohol/prescription abuse and mental disorders. The original assessment was a 10-item questionnaire that was developed by Dr. Lynn Webster to serve as another tool to help with opioid-use assessments. Preadolescent sexual abuse is only weighted for females since when reviewed, researchers did not observe any difference in the response when weighted in men. Scores greater than 8 indicate a high risk for potential abuse, 4 to 7 means moderate risk, and scores 3 or less indicate low risk.11 The ORT was condensed to five questions.12 In the study, the revised version was found to be 85.4% sensitive, with 85.1% specificity.12 One benefit of the ORT is that it is part of MDCalc.8 The ORT may not absolutely predict potential abuse by itself, but it can help guide clinicians in their decisions concerning appropriate treatment for the patient.8

The SOAPP-R was developed to help screen patients who are at risk for long-term opioid abuse. This tool was developed with the help of an expert panel of pain and addiction specialists, identifying the characteristics of opioid abuse and rating their hierarchy. It is a 24-question, self-administered tool with a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 68%.13 The maximum score is 96. A score of 18 or greater means the patient is at higher risk for abuse of opioids.8 This tool should be used with clinical assessments to help guide the clinician’s treatment program. When comparing ORT and SOAPP for predicting risk of abuse in patients taking opioids for chronic pain, SOAPP with clinical assessment was more sensitive.14

When meeting with patients on long-term opioids, providers should determine if opioid tapering is recommended and use the clinical assessment tools that have been discussed previously.15 The guidelines recommend discontinuation of opioids if there is no clinically meaningful improvement in pain and function, treatment resulted in a severe adverse event, or the patient has a history or current substance-use disorder, excluding tobacco.4 In patients who are not showing abuse behavior or there is a concern for harm to the patient, tapering may not be appropriate. There is concern for providers being pressured, whether by insurance companies or guidelines stating that patients are at increased risk of overdose if they are over a certain morphine equivalent. Other considerations for tapering of opioids are patients concurrently treated with a benzodiazepine and a hypnotic, which puts them at increased risk of overdose.1,14

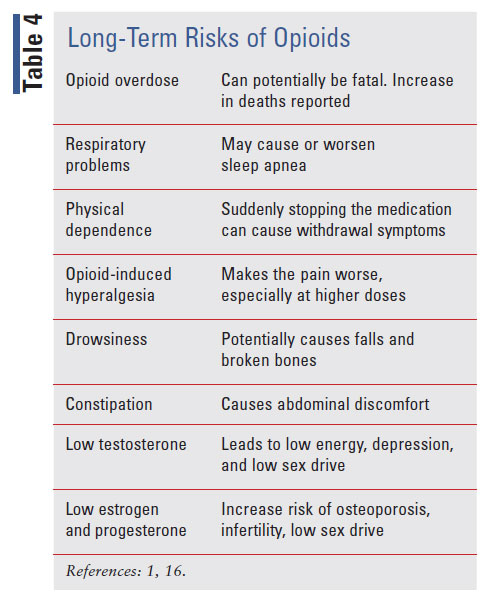

Patients should be made aware of the long-term complications of opioids, as shown in TABLE 4. These complications include constipation, nausea, somnolence, memory loss, increase risk of falls, respiratory depression, effects on hormones that can lead to infertility, sexual dysfunction, osteoporosis, depression, hyperalgesia, and mortality.1,16

Providers should enter the conversation with no bias. A study showed that patients who have a substance use disorder feel they are not treated the same as others and desire the same respect that is extended to other patients.30 The conversation should be generalized and without emotions.8 The following components were found to be helpful when discussing the tapering process with patients.17

Rationale for Tapering

Explaining the reasoning for tapering to the patient makes it individualized.17 The Canadian National Pain Centre at McMasters has a good, patient-friendly document that discusses points for tapering. Patients may feel they were being punished when told they need to taper, even if they were taking the medications as prescribed.17 Most of the studies and commentary reports making the conversation specific to the patient. Clinicians should explain to the patient the tools and assessments used to determine why there was a need for tapering. A common theme also was to not tell the patient the tapering is the result of the opioid crisis; to them, this means nothing. Using either the ORT or SOAPP-R to start the conversation, the provider can then assess for patients who are at increased risk of abuse. The use of these tools does not predict abuse; rather, they indicate that these patients have risk factors that can make them more sensitive to abuse issues, whether environmental or genetic.13

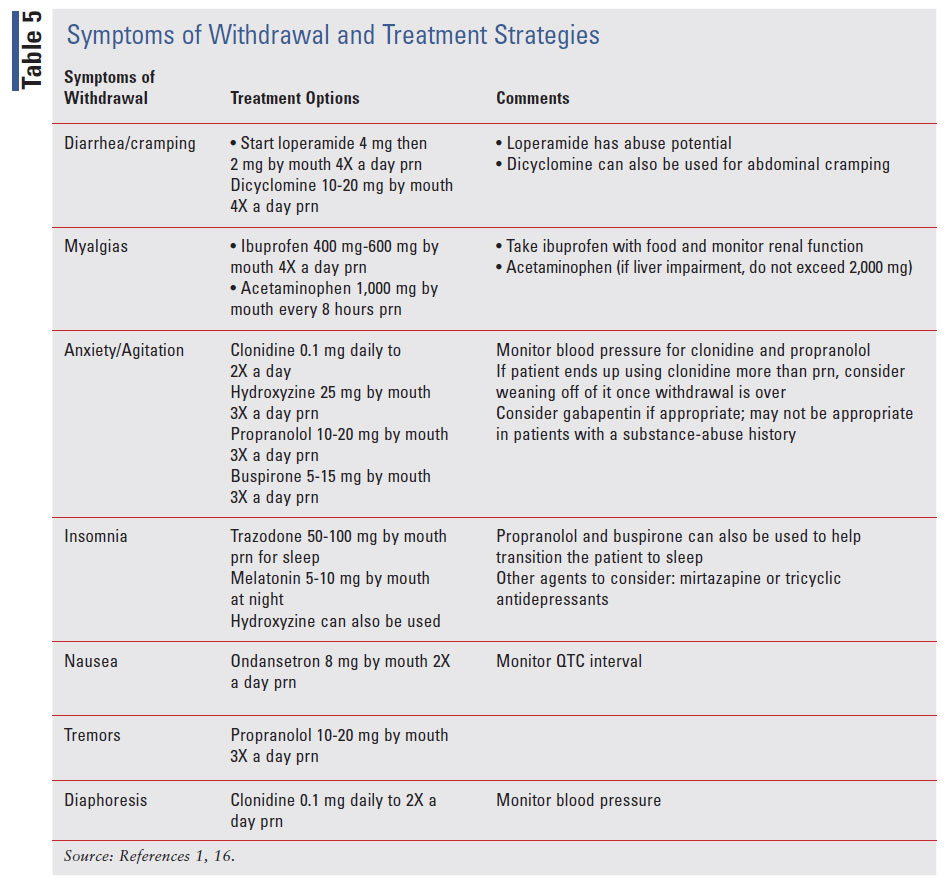

Shared Decision-Making

Including the patient as part of the process helps to establish trust between provider and patient.2 There are a lot of fears around the process of tapering.17 Patients wonder if their pain will be controlled.17 Withdrawals can be difficult to explain, and patients may be hesitant, especially if they have experienced prior withdraws.17 A pharmacist can help with painmanagement education to help establish that trust with the patient.30 TABLE 5 shows the symptoms of withdrawal and treatment options available for symptom management.1,4,5 The last set of assessment tools that can be beneficial when tapering down patients on their opioid dose are the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS) and the Clinical Institute Narcotic Assessment (CINA). Both are 11-item scales that assess questions based on patients’ behaviors and observation by clinician to tell how severe withdrawal is. The CINA scores range from 0 to 31, and the higher the score, the more severe withdrawal is. Scores using the COWS range from 0 to 47, and 5 to 12 are considered mild, 13 to 24 are moderate, 25 to 36 are moderately severe, and >36 is considered severe withdrawal.18 There is potential for bias since patients report how they feel.18

Assessment and Screening Tools

Taking the time to explain the tools being used to assess for withdrawals and what to expect can help the patient. The pharmacist has more time to answer questions about withdrawals and treatment options than the provider.30,31 The pharmacist should discuss with the patient what the realistic goals of pain management are. Again, it is important to reiterate to the patient that the focus of their treatment is to help better control pain so they feel that they are functional, emotionally and physically. These expectations can include improvements in cognition and pain/functionality.

Negotiation

Negotiating when there is a disagreement between the provider and patient may be necessary. Disagreements can happen when the patient and provider are not at a mutual point in the tapering plan. The provider needs to be willing to offer explanations while engaging the patient and reassuring the patient that it is a partnership.1,16 One study showed than when the provider and patient talk and listen to each other, they were able to come to a consensus.17 The disagreement may also stem from a urine drug screen and how the provider interprets or discusses the results of an unexpected detection in the screening. A resource that providers can use is My Top Care.19 This website helps provides information for false positives and other scenarios.

Abandonment can come in the form of a false-positive urine screen.17 Again, communication is key between the provider and the patient. Additionally, the disagreement can arise when the patient is not ready to taper down to the next dose and the clinician feels that it is time to decrease. These discussions between the provider and patient should be respectful and demonstrate understanding.31 Motivational interviewing can help the tapering discussion when there is a disagreement.20

Assurance and Mental Health

Abandonment can be detrimental to the patient. Abandonment can cause more harm to the patient and result in withdrawal due to opioids not being prescribed, causing further mental stress and even contributing to the patient being suicidal.14 Assuring that the provider did not abandon the patient in this process is important. The patient’s mental health is also to be addressed for successful weaning.1,16 Patients who have underlying mental health conditions should be assessed for therapy. Making sure that providers treat that aspect of the disease helps ensure a successful process. The ORT is also a good tool to use for assessing mental health history. Patients can be further screened using the PHQ-9, an assessment for depression, or GAD-7, an assessment tool for anxiety. All of the guidelines state that if these conditions are not treated appropriately, opioid use or tapering can be negatively impacted.1,5 Some of the patients who are affected by opioid use disorder can be from groups who are already sensitive to issues such as discrimination due to race, substance-abuse history, and economic hardships.31 Due to multiple comorbid conditions, it is recommended that a multidisciplinary approach may be beneficial in the tapering process.5 A pharmacist can touch base with patients between visits to assess withdrawal or answer any medication questions. A therapist can help with behavioral therapy for patients with mental health needs. Finally, a social worker can help address some of the inequities and connect these patients with resources from the community.

Other aids to assist with tapering include videorecorded narrative clips discussing opioid tapering. Greater patient engagement with the clip, but not age or gender concordance with the storyteller, was associated with greater perceived persuasiveness for promoting opioid tapering. Patient narratives that are engaging and clinically relevant are likely to be persuasive, regardless of storyteller demographics.21

Tapering Methodology

There are multiple methods that can be considered when tapering. Immediate discontinuation may be needed if diversion is involved.4 A rapid taper over a 2- to 3-week time frame may be appropriate if the patient has a substance use disorder.4 A slow taper can start with less than 10% of the original dose per week with regular monitoring. Another strategy is an understanding that an opioid decrease is made with the agreement between the provider and patient. In this strategy, the patient would be informed that once the decrease is made an increase from that dose will not occur.4 Other taper strategies include reduction of doses by 5% to 10% every 1 to 2 months, depending on how the patient tolerates it.1,4,5,16 Use the PEG to assess how patients are at each reduction and the COWS scale to assess for withdrawal. If withdrawal symptoms are present, mitigating them will help with the wean. TABLE 5 shows treatment options for symptoms.1,3 Acute opioid withdrawal in ambulatory patients is not considered lethal, but the symptoms can be bothersome.1

Patients who do not tolerate the tapering process may be designated for a slower taper. Patients can feel some side effects from tapering even after they are off opioids up to 6 months post discontinuation, so a slow taper may be beneficial.4 Buprenorphine may have a role in patients unable to tolerate the wean. It is a partial mu-receptor agonist that has an advantage over other opioids in that the risk of respiratory depression plateaus as the dose increases.14 Buprenorphine can be a good option for patients with poor pain control.14 The patch is approved for the treatment of pain. Providers need specialized training and a waiver from the DEA to prescribe other forms of buprenorphine (a waiver is not required for the patch formulation).14

After discussing the plan and what the patient can expect, the provider can bring in other disciplines to help manage the process. The pharmacist can help the provider check in with the patient, answer questions regarding the taper, and make interventions as appropriate. One study showed that a pharmacist can be the communicator between the patient and provider. The pharmacist met with the patient, and if an intervention was identified, the provider was contacted to discuss the intervention. Furthermore, the pharmacist contacted the patient to make the intervention after discussion with the provider.21 Local community pharmacists may also help in this process. They can educate and ask questions when the patients pick up their medications. They can help review drug interactions for patients who have multiple providers prescribing medications. Also, community pharmacists can dispense naloxone in many states, if needed.30

Tapering requires a lot of communication, frequent assessment, and frequent follow-up appointments. Some concerns with the role of the pharmacist in this process have been identified. Pharmacists are thought of as accessible; however, one study looking at patients’ perspectives revealed that pharmacists are sometimes thought of as too busy, so patients may not seek advice. Additionally, patients may not be aware of the clinical role a pharmacist is able to perform, including drug knowledge and counseling.31 Some patients feel that community pharmacists may not have enough time to provide effective education.31

Naloxone

Naloxone is a highly competitive, mu-opioid receptor antagonist that reverses the central and peripheral effects of exogenous and endogenous opioids within 2 to 5 minutes of administration. Naloxone can be administered through several different routes, including IM, SC, and intranasal.22,23 The CDC provides guidance in offering naloxone and overdose-prevention education for patients and their household for patients who are taking at least 50 morphine milligram equivalents a day.1 There has been a decreased risk of death by opioid overdose since community-based programs have distributed naloxone.1

Impact of COVID-19

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, which was declared by the WHO on March 11, 2020, has impacted the medical care provided to patients. Mental health concerns and substance use–related harms have risen amid the global pandemic due to a variety of factors, including stay-at-home orders, social distancing, fear of sickness and death, loss of employment, economic stress, and loss of family and friends due to illness.24 In April 2020, one in seven adults in the U.S. reported serious psychological distress.25

Another study showed 13.3% of adults had started or increased substance use to cope with stress or emotions related to the pandemic, while 30.9% had symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorders and 10.7% had considered suicide in the past month.25 People with opioid use disorder may be at higher risk of complications from COVID-19 given the immunosuppressive nature of opioids.26,27

In March 2020, the Office for Civil Rights at the HHS allowed the use of nonpublic-facing audio or video communication products. Medicare now allows reimbursement for telehealth services. Since COVID19, a face-to-face visit for controlled substances is no longer required, and telemedicine is allowed to prescribe these medications. The opportunity to use telemedicine has the potential to manage more people and expand access to care.28 The federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration allowed stable patients with opioid use disorder in opioid-treatment programs to take home a 28-day supply of medication or a 14-day supply for less stable patients.26

One study showed a reduction in prescriptions for opioid analgesics, and buprenorphine use for opioid use disorder decreased among new patients during the pandemic (but not among existing patients receiving therapy).28 The ORT and SOAPP-R assessment tools can be conducted through telemedicine. An in-person visit is recommended if a patient scores greater than 18 on the SOAPP-R and greater than 8 on the ORT.29

Patients who use chronic opioids and are hospitalized for COVID-19 and who need to be intubated may require prolonged time on mechanical ventilators, and this may make extubating a greater challenge due to decreased respiration. Patients using chronic opioids require opioids during hospitalization to prevent opioid-withdrawal syndrome, and there is an increased risk of opioid-induced respiratory depression. Additionally, patients needing opioids have potential interactions with other necessary medications, including certain antibiotics or other drugs, which may be associated with prolongation of the QTc and require closer monitoring during hospitalization. Clinicians may want to consider providing studied nonopioid alternatives and nondrug approaches for pain management in light of the COVID-19 pandemic in patients with opioid use disorder. Additional research is needed to assess the impact of COVID-19 on long-term opioid use.27

Conclusion

The opioid epidemic has caused a shift in the prescribing of opioids. It has changed the way clinicians provide pain relief in noncancer pain. Providers are not required to assess pain as a chronic disease. When seeing patients, they should reassess the need for the pain medication and, if appropriate, use validated tools to taper therapy. Communication plays a large part in establishing trust and a partnership with the patient, resulting in a more successful taper. Pharmacists have a role in this process.

The content contained in this article is for informational purposes only. The content is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice. Reliance on any information provided in this article is solely at your own risk.

REFERENCES

- Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain–United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(1):1-49. Erratum in: MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(11):295.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. What is the U.S. opioid epidemic? www.hhs.gov/opioids/about-the-epidemic/index. html. Accessed December 1, 2021.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. HHS Acting Secretary declares public health emergency to address national opioid crisis. www.hhs.gov/about/news/2017/10/26/hhs-acting-secretarydeclares-public-health-emergency-address-national-opioid-crisis.html. Accessed December 4, 2021.

- Washington State Agency Medical Directors’ Group (AMDG). Interagency guideline on prescribing opioids for pain. 2015. https:// agencymeddirectors.wa.govFiles/2015AMDGOpioidGuideline.pdf. Accessed November 23, 2021.

- Busse JW, Craigie S, Juurlink DN, et al. Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain. CMAJ. 2017;189:E659-E666.

- Wenger S, Drott J, Fillipo R, et al. Reducing opioid use for patients with chronic pain: an evidence-based perspective. Phys Ther. 2018;98(5):424-433.

- Austin RC, Fusco CW, Fagan EB, et al. Teaching opioid tapering through guided instruction. Fam Med. 2019;51(5):434-437.

- Ducharme J, Moore S. Opioid use disorder assessment tools and drug screening. Mo Med. 2019;116(4):318-324.

- Krebs EE, Lorenz KA, Bair MJ, et al. Development and initial validation of the PEG, a three-item scale assessing pain intensity and interference. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(6):733-738.

- Von Korff M, DeBar LL, Krebs EE, et al. Graded chronic pain scale revised: mild, bothersome, and high-impact chronic pain. Pain. 2020;161(3):651-661.

- Brott NR, Peterson E, Cascella M. Opioid Risk Tool. [Updated 2021 May 19]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Cheatle MD, Compton PA, Dhingra L, et al. Development of the revised opioid risk tool to predict opioid use disorder in patients with chronic nonmalignant pain. J Pain. 2019;20(7):842-851.

- Butler SF, Fernandez K, Benoit C, et al. Validation of the revised Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain (SOAPP-R). J Pain. 2008;9(4):360-372.

- Moore TM, Jones T, Browder JH, et al. A comparison of common screening methods for predicting aberrant drug-related behavior among patients receiving opioids for chronic pain management. Pain Med. 2009;10(8):1426-1433.

- Covington EC, Argoff CE, Ballantyne JC, et al. Ensuring patient protections when tapering opioids: Consensus Panel Recommendations. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(10):2155-2171.

- Oxford Pain Management Centre. Guidance for opioid reduction in primary care. 2017. www.ouh.nhs.uk/services/referrals/pain/documents/gp-guidance-opioid-reduction.pdf. Accessed February 18, 2022.

- Matthias MS, Johnson NL, Shields CG, et al. “I’m not gonna pull the rug out from under you”: patient-provider communication about opioid tapering. J Pain. 2017;18(11):1365-1373.

- Nuamah J, Sasangohar F, Erraguntla M, Mehta RK. The past, present and future of opioid withdrawal assessment: a scoping review of scales and technologies. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2019; 19:113.

- Clinicians resources and Tools. My Top Care. www.mytopcare. org/. Accessed December 21, 2021.

- Hah JM, Trafton JA, Narasimhan B, et al. Efficacy of motivational-interviewing and guided opioid tapering support for patients undergoing orthopedic surgery (MI-Opioid Taper): a prospective, assessor-blind, randomized controlled pilot trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;28:100596.

- Lagisetty P, Smith A, Antoku D, et al. A physician-pharmacist collaborative care model to prevent opioid misuse. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;7(10):771-780.

- Kim HK, Nelson LS. Reducing the harm of opioid overdose with the safe use of naloxone: a pharmacologic review. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2015;14(7):1137-1146.

- Rzasa Lynn R, Galinkin JL. Naloxone dosage for opioid reversal: current evidence and clinical implications. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2018;9(1):63-88.

- Marroquin B, Vine V, Morgan R. Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: effects of stay-at-home policies, social distancing behavior, and social resources. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113419.

- Czeisler ME, Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic–United States, June 24-30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(32):1049-1057.

- Mitchell M, Shee K, Champlin K, et al. Opioid use disorder and COVID-19: implications for policy and practice. JAAPA. 2021;34(6):1-4.

- Shah R, Kuo YF, Baillargeon J, Raji MA. The impact of longterm opioid use on the risk and severity of COVID-19. J Opioid Manag. 2020;16(6):401-404.

- Currie JM, Schnell MK, Schwandt H, Zhang J. Prescribing of opioid analgesics and buprenorphine for opioid use disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4):e216147.

- Ogilvie CB, Jotwani R, Joshi J, et al. Review of opioid risk assessment tools with the growing need for telemedicine. Pain Manag. 2021;11(2):97-100.

- Murphy L, Ng K, Isaac P, et al. The role of the pharmacist in the care of the patients with chronic pain. Integr Pharm Res Pract. 2021;10:33-41.

- Fatani S, Blake D, D’Eon M, El-Aneed A. Qualitative assessment of patients’ perspectives and needs from the community pharmacists in substance use disorder management. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2021;16(1):38. Prevention and Policy. 2021;16:38.