Neuropsychiatric Complications of Psoriasis and Its Treatment

RELEASE DATE

January 1, 2023

EXPIRATION DATE

January 31, 2025

FACULTY

Brooke Barlow Neurocritical Care Clinical Pharmacy Specialist Memorial Hermann The Woodlands Medical Center The Woodlands, TexasDISCLOSURE STATEMENTS

Dr. Barlow has no actual or potential conflicts of interest in relation to this activity. Postgraduate Healthcare Education, LLC does not view the existence of relationships as an implication of bias or that the value of the material is decreased. The content of the activity was planned to be balanced, objective, and scientifically rigorous. Occasionally, authors may express opinions that represent their own viewpoint. Conclusions drawn by participants should be derived from objective analysis of scientific data.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

Pharmacy

Pharmacy

Postgraduate Healthcare Education, LLC is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education as a provider of continuing pharmacy education.

UAN: 0430-0000-23-011-H01-P

Credits: 2.0 hours (0.20 ceu)

Type of Activity: Knowledge

TARGET AUDIENCE

This accredited activity is targeted to pharmacists. Estimated time to complete this activity is 120 minutes.

Exam processing and other inquiries to:CE Customer Service (800) 825-4696 or cecustomerservice@powerpak.com

DISCLAIMER

Participants have an implied responsibility to use the newly acquired information to enhance patient outcomes and their own professional development. The information presented in this activity is not meant to serve as a guideline for patient management. Any procedures, medications, or other courses of diagnosis or treatment discussed or suggested in this activity should not be used by clinicians without evaluation of their patients’ conditions and possible contraindications or dangers in use, review of any applicable manufacturer’s product information, and comparison with recommendations of other authorities.

GOAL

To educate pharmacists about the epidemiology, manifestations, risk factors, and role of a pharmacist in the management of patients with psoriasis and mental health disorders or other neurologic complications from pharmacological therapy.

OBJECTIVES

After completing this activity, the participant should be able to:

- Describe the epidemiology and pathophysiology of neuropsychiatric complications associated with psoriasis.

- Discuss risk factors and comorbidities likely to contribute to neuropsychiatric disturbances.

- Outline medications used for psoriasis and the impact on the development of neuropsychiatric conditions.

- Highlight the role of the pharmacist in optimizing medication regimens and providing critical patient education on the risks of neuropsychiatric complications with psoriasis pharmacotherapy.

ABSTRACT: Psoriasis is an autoimmune, dermatologic condition that is highly visible, and the symptoms can diminish self-esteem and impact mental health and social life. A diagnosis of psoriasis can negatively influence a patient’s quality of life, with increased psychological morbidities that often go unrecognized. With an incidence as high as 24% to 90%, mental disorders are an important part of the challenge of psoriasis. Disease biology and medications can contribute to these psychological comorbidities. Managing the psychosocial part of the illness, along with its physical aspect, has been shown to result in improved patient outcomes.

Psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated inflammatory skin condition with a prevalence of 3% in adults in the United States, translating into more than 7.5 million adults.1 Psoriasis is classified into various subtypes depending on the distinct subset of symptoms and characteristics, with the most common subtype being plaque psoriasis, which manifests as scale-like silver plaques associated with dryness and itching.2 Any area of the body can be affected, with some patients presenting with symptoms in visible regions like the face and arms and others having manifestations in more sensitive regions like skin folds or inguinal region. Furthermore, psoriatic arthritis is a subtype of psoriasis that presents with both skin and systemic involvement, primarily inflammation of the joints. Psoriasis follows a relapsing course that can negatively impact patient quality of life (QOL). Furthermore, patients often go undiagnosed or untreated given the general embarrassment over presenting their physical symptoms.3 Although psoriasis is primarily considered a skin condition, it is increasingly considered a systemic disease with an impact on many organs, including the cardiovascular, metabolic, and neurologic systems. The factors contributing to the development of multiple comorbid conditions in psoriasis are multifactorial and include the inherent immune process as well as medications to treat the disease.3 Recently, there have been increased efforts to evaluate patients for potential neurologic impacts of psoriasis, both the development of mental health conditions and neurological sequelae of the disease.4 Neurologic complications in psoriasis range broadly from mood disorders such as depression, anxiety, fatigue, or cognitive impairment to neurologic conditions such as tremors and stroke.3,5 Emerging evidence suggests depression and anxiety could also perpetuate the risk of cardiovascular disease, revealing the interplay between the comorbidities seen in psoriasis.3 The physical and cosmetic manifestations of psoriasis contribute to substantial psychological strain affecting the personal, social, and sexual lives of patients, impacting overall QOL.5 Addressing mental health is a critical component of the comprehensive care of patients with psoriasis, as they are more than 1.5 times likely to have depression than controls.3 This review will focus on psychiatric mood comorbidities in psoriasis, primarily depression, as well as drug-related neurologic conditions.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

In general, it is estimated that the prevalence of psychiatric conditions in psoriasis ranges from 24% to 90%.6 In a cohort study of 2,391 patients, depressive symptomatology was observed in 62% of patients with psoriasis, illustrating that over half of the population with this condition is predisposed to developing collateral depression.7 Overall, the prevalence of depression and anxiety in those with psoriasis is significantly higher than the general population.3,8 In comparison to other dermatologic conditions, psychiatric comorbidities are higher, and overall QOL scores are substantially lower.7,8 The risk for suicidal ideations associated with depression in psoriasis is unclear; however, mounting evidence suggests that the risk is greater than in those without psoriasis. One retrospective cohort study conducted in 127 patients with psoriasis revealed that 5.5% had suicidal ideations and nearly 10% wished they were dead.8 Conflicting evidence exists in a systematic review that determined the risk ratio for suicide was no different than controls, regardless of severity of the disease.9 Nevertheless, awareness and identification of mental health issues in these patients can help mitigate the risks of suicidal ideations.3

CORRELATION BETWEEN PSORIASIS AND DEPRESSION

Due to the physical symptoms of the disease, such as diffuse scaly rash, itching, redness, and the sensitive areas involved, patients with psoriasis can suffer from embarrassment, low self-esteem, anxiety, and depression.4 Unfortunately, emotional symptoms of stress of anxiety are a trigger for disease flare and contribute to progression of psoriatic lesions, leading to a difficult cycle of events.3,5 In fact, studies have observed a positive correlation between stress and depressive symptoms with the risk of psoriasis flare-ups and pruritus severity as assessed by Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) scores.9-11 Given that the lesions are itchy and can appear on any area of the body, patients may have difficulty with coping with the physical manifestations, leading to anxiety, social isolation, and subsequent depression. Patients with psoriasis feel stigmatized over myths that psoriasis is a contagious disease, resulting in patients refraining from social situations, exacerbating depressive symptoms.12,13 Although there are a paucity of large analyses evaluating the prevalence of mood disorders in psoriasis, the American Academy of Dermatology and National Psoriasis Foundation have jointly developed a guideline for Management and Treatment of Psoriasis with Awareness and Attention to Comorbidities to provide healthcare providers with increased attention and guidance for evaluating patients with psoriasis and mental health issues.3 The guidelines acknowledge that although some patients are hesitant to discuss or reveal their psoriasis to providers due to fear or stigma associated with the diagnosis, patients who go untreated have an even greater risk of developing depression.10,13 The guidelines review multiple studies on how symptom-targeted treatments can reduce depression severity, resulting from reduction in visible or symptomatic lesions.3 Therefore, it is important for providers to have open discussion with patients regarding the impact of treating the disease on improvements of self-confidence and overall QOL.13,14

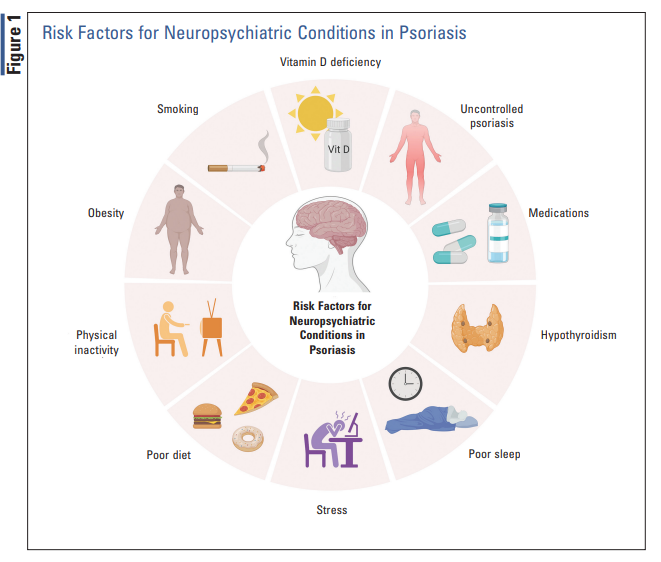

RISK FACTORS FOR NEUROPSYCHIATRIC CONDITIONS

Vitamin D deficiency is separately involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis and depression.15 An important trigger for psoriasis flares is exposure to excessive sunlight. In return, reduced exposure of sunlight in patients with psoriasis increases the risk of a vitamin D deficiency. This is a critical connection given the pathological role of vitamin D and the integumentary

immune system. In normal skin conditions, vitamin D metabolites play a role in differentiation and growth of keratinocytes. In patients with psoriasis, low vitamin D concentrations reduce the availability of circulating T regulatory cells, leading to uncontrolled T-helper (Th) cell activation. Once vitamin D levels are restored, T regulatory cells are regenerated, and there is a resulting immunomodulatory effect through suppression of Th1 and Th17 responses.15 Vitamin D deficiency is also linked to depression, with low levels resulting in higher rates of depression, as is observed in patients with seasonal depression. There is also a link between depression, vitamin D, and inflammation, with low vitamin D levels resulting in increased concentrations of inflammatory cytokines that are critical to the pathogenesis of depression.16 Therefore, this complex interplay of the brain, inflammation, and vitamin D has been explored and exploited. As a result of this pathophysiology, it is proposed that in skin conditions such as psoriasis, patients may benefit from vitamin D supplementation, which can aid in regenerating normal skin conditions.17 Therefore, vitamin D deficiency appears to play a role in the pathogenesis of both psoriasis and depression. Beyond the role of vitamin D, additional factors that can influence the risk of neuropsychiatric conditions are listed in FIGURE 1. These risk factors typically coexist, and the presence of one exacerbates or results in the development of another. For example, medications as well as physical inactivity due to physical symptoms of severe disease or self-esteem issues can result in obesity and other cardiometabolic conditions, which perpetuate the risk of depression.3 Medications such as steroids can result in poor eating and sleep, which will contribute to stress. Furthermore, given the immune nature of psoriasis, coexisting hypothyroidism related to immune dysfunction can result and, when left untreated, can contribute to depressive symptoms. All in all, the resulting neuropsychiatric conditions in psoriasis are multifactorial.

DRUG-RELATED CAUSES

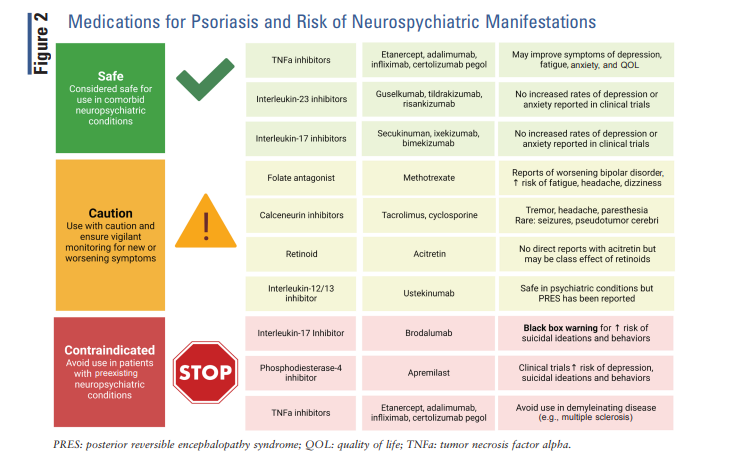

Aside from disease-, lifestyle-, and comorbidity-related causes, medications used for the treatment of psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis can contribute to or exacerbate neuropsychiatric conditions. Pharmacists play a critical role in identifying potential medications that can cause or worsen neuropsychiatric conditions and aid in optimization of pharmacotherapy for these patients FIGURE 2.

ORAL SYSTEMIC THERAPIES

Apremilast: Apremilast is an oral phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor indicated for patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis who are refractory or have contraindications to other systemic therapies.18 Evidence from clinical trials and postmarketing raised safety concerns regarding a heightened risk of depression and suicidal ideations or behaviors with apremilast therapy, including cases of completed suicide.19 Rates of depression range from 1.3% to 2.8% in clinical trials, with 65 cases of suicidal behaviors reported from FDA approval in 2014 to 2016, prompting an update to package insert labeling to include warning of these risks.18 A careful history of symptoms and past medical history prior to prescribing apremilast to evaluate for psychiatric symptoms or preexisting psychiatric condition is recommended, with avoidance of use if any are present. A patient-centered discussion on the risk of psychiatric symptoms during therapy coupled with vigilant monitoring during treatment is paramount to mitigate adverse psychiatric consequences. Discontinuation of apremilast is warranted if new or worsening psychiatric symptoms, or any suicidal ideations or behaviors, occur during treatment.18

Methotrexate: Methotrexate is a folate antagonist that exhibits nonspecific, potent anti-inflammatory effects and effectively ameliorates inflammation and musculoskeletal pain associated with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Methotrexate dosed once weekly for rheumatologic conditions is associated with fewer side effects than dosages used in oncology but remain high and potentially life threatening in the case of hematologic, hepatic, or nephrotoxicity. Neurologic complications on low doses appear limited to dizziness, headache, and fatigue. Methotrexate has also been associated with increased rates of depression and exacerbations of bipolar disorder in patients with psoriasis.20,21 It is hypothesized that the interference of folate metabolism alters the metabolic pathways of S-adenylmethoinine (SAMe)/Sadenylhomocysteine, critical intermediaries for neurotransmitter biosynthesis.22 Risk factors for neuropsychiatric disturbances with methotrexate include female sex, larger body surface area involvement, self-distraction, and behavior disengagement.20 Guidance on management of methotrexate-induced neurologic effects is sparse. All patients on methotrexate should receive daily folic acid supplementation to mitigate adverse hematologic consequences, such as anemia, that could exacerbate fatigue or other neurologic symptoms. For patients with persistent or psychological distress that impacts QOL, reduced dosing or transition to an alternative disease-modifying therapy may be considered.

All patients on methotrexate should receive daily folic acid supplementation to mitigate adverse hematologic consequences, such as anemia, that could exacerbate fatigue or other neurologic symptoms.

Calcineurin Inhibitors: Cyclosporine and tacrolimus are calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) traditionally used in the setting of transplant, possessing potent immunomodulatory effects that are advantageous in suppressing inflammation in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Similar to methotrexate, CNIs are associated with a multitude of dose-limiting adverse effects, such as hypertension, nephrotoxicity, and malignancy. Neurologic complications occur in up to 40% of patients on CNIs, with symptoms including headache, paresthesia, tremors, and visual disturbances often more pronounced with tacrolimus treatment.23 Though rare, there have been cases of pseudotumor cerebri and seizures associated with CNIs.24 Interestingly, low-dose, short-term cyclosporine (3 mg/kg/day) use may reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression and improve QOL.25,26 However, these effects appear to be secondary to improved psoriasis symptom control rather than a direct protective effect of the medication. Severe neurologic complications such as seizures or pseudotumor cerebri warrant discontinuation; however, other complications of cyclosporine are often mild and self-limiting and may not warrant discontinuation unless impacting a patient’s daily functioning. Dose reduction or transition to a controlled-release product can be considered to minimize tacrolimusinduced tremors.27

Acitretin: Acitretin is an oral vitamin A derivative (retinoid) indicated for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis when contraindications to alternative oral systemic therapies are present. Headache is the most prominent neurologic adverse effect of acitretin that usually occurs within 1 to 6 weeks of treatment initiation.28 Though rare, cases of pseudotumor cerebri have been reported with acitretin and should be suspected if persistent, severe headaches are accompanied by nausea, photophobia, vomiting, or blurred vision. Sensorimotor polyneuropathy can also occur with acitretin, reversible upon drug withdrawal.29 Depression and risk of suicidal ideations are listed in the package labeling for acitretin; however, this warning is largely based on case reports of isotretinoin. There are a lack of clinical studies evaluating a causality or reports of acitretin-associated psychiatric complications, and it appears labeling is based on drug class rather than direct reports associated with acitretin use.30 Nonetheless, in the absence of any direct clinical data, patients on acitretin should be informed of the potential risk of depression and suicidal ideations associated with treatment with consideration to discontinuation if symptoms occur.

Biological Therapies

TNFα inhibitors have become a mainstay therapy for psoriasis and are proven to be more effective than traditional disease-modifying therapies that provide durable symptom control. Furthermore, randomized, controlled trial data show TNFα inhibitors are more effective than conventional oral therapies for improving anxiety, depression, and overall QOL in moderate-to-severe psoriasis.31,32 A phase III trial of 618 patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis demonstrated treatment with etanercept significantly improved fatigue scores and symptoms of depression compared with placebo, without an increase in adverse effects.33 Reduction in joint pain and clearance in skin lesions were correlated with greater improvements in fatigue and depression scores, respectively.33 These findings are consistent with a nationwide cohort study of 980 patients initiated on TNFα inhibitors demonstrating a 40% reduction in antidepressant use after TNFα inhibitor initiation compared with continuation of nonbiologic disease-modifying therapy alone.21 Age younger than 45 years, absence of psoriatic arthritis, not taking concurrent methotrexate, and continued biological therapy were patient characteristics associated with more rapid clinical improvement in depression and insomnia.21 Overall, these data suggest adding a TNFα inhibitor for improved symptom control may provide additional benefit in improving fatigue and depressive symptoms associated with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. TNFα inhibitors have been associated with newonset or exacerbation of comorbid demyelinating disorders, such as multiple sclerosis, optic neuritis, and neurologic manifestations of vasculitis.34 The exact mechanism of TNFα-related demyelinating disorders remains unknown but is proposed to be secondary to increased level of reactive T-cells in the cerebrospinal fluid and inability of TNFα inhibitors to cross the blood-brain barrier.34 TNFα inhibitors should be avoided if possible or used with extreme caution in patients with pre-existing or new-onset demyelinating disorders. Rare cases of transverse myelitis have been reported with etanercept use. Transverse myelitis should be suspected in patients presenting as back pain, lower extremity weakness, and urinary and fecal incontinence and, if diagnosed, warrants TNFα inhibitor discontinuation.35

Interleukin (IL)-17 Antagonists: Secukinumab, ixekizumab, bimekizumab, and brodalumab are human monoclonal antibodies targeted against IL-17 and approved for use in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Clinical trial data suggest no increased risk of psychiatric manifestations, including depression, anxiety, or suicidal behaviors associated with secukinumab, ixekizumab, or bimekizumab use.36 On the contrary, in the clinical trials evaluating brodalumab, increased mood disturbances and suicidal thoughts and ideations, including four completed suicides, were reported, prompting a black box warning for increased risk of psychiatric disturbances associated with its use.37 Brodalumab is only available through a restricted risk evaluation and mitigation program that requires careful evaluation prior to initiation and frequent assessment for risk of suicide during treatment.37

Interleukin-12 and -23 Antagonist: Ustekinumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody with a dual target against the p40 subunit of IL-12 and IL-23. Psychiatric complications in clinical trial data appear rare, with no increased suicide or depression risk compared with placebo. Most common neurologic manifestations include headache and fatigue, reported in 5% and 3% of patients in clinical trials, respectively. A rare but serious neurologic adverse effect of ustekinumab is posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES). Two cases of PRES presenting as headaches, seizures, visual disturbances, and hypertension were reported in clinical trial data, warranting drug discontinuation. If PRES occurs, permanent withdrawal of ustekinumab is recommended without rechallenge.38

Interleukin-23 Antagonist: Guselkumab, tildrakizumab, and risankizumab each target various subunits of IL-23. In the large clinical trials evaluating these agents for psoriasis, no cases of depression, suicidal ideation, or other psychological manifestations were reported.36

ROLE OF THE PHARMACIST

Management strategies to mitigate depression and anxiety in patients with psoriasis require careful patient history, exam, and a comprehensive medication review to assess for the underlying etiology. Nonpharmacologic treatments may include routine exercise, sleep regulation, diet modification, and stress management, all of which have shown to positively impact symptoms of depression and anxiety. Patient referral to a psychiatrist in the setting of depression and anxiety is of critical importance to ensure appropriate coping mechanisms can be employed as well as considerations to initiate of psychotropic medication, if warranted. Identification and management of underlying conditions that may cause or contribute to depression, such as hypothyroidism and vitamin D deficiency, are imperative prior to considering addition of psychotropic therapy. Optimizing disease control in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis is also critical to improve QOL for those whose depression is secondary to worsening disease manifestations. A careful medication review should be performed, with discontinuation of medicationinduced causes of worsening neurologic or psychiatric symptoms.39 Considerations to initiation of antidepressant or anxiolytic medication in discussion with the patient’s goals of treatment can also be considered. Pharmacists are integral in screening and monitoring patients on nonbiological and biological therapies for psychiatric symptoms as potential adverse effects of therapy or worsening of disease control, which can then permit for medication optimization to decrease disease burden or address neuropsychiatric complications. Pharmacists should ensure patients are educated and informed on the risks associated with disease-modifying therapies and to seek medical attention immediately if any symptoms of depression, suicidal ideations, or behaviors develop.

CONCLUSION

Neurologic and psychiatric manifestations are common in psoriasis and may be secondary to uncontrolled inflammation as a progression of the disease, underlying comorbidities, or medication-related. Identification and management of neuropsychiatric complications in psoriasis are critical to improve QOL and minimize the risk of disabling, potentially fatal complications. Pharmacists play a critical role in the care of patients with psoriasis from initial evaluation of appropriate therapies, identification of medication-induced causes, and optimization of disease-modifying therapies to patient education on the risks associated with psoriasis therapies.

REFERENCES

- Armstrong AW, Mehta MD, Schupp CW, et al. Psoriasis prevalence in adults in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(8):940-946.

- Ritchlin CT, Colbert RA, Gladman DD. Psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:957-970.

- Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(4):1073-1113.

- Nery R, Carvalho M, Filho EM, et al. Neurological comorbidities in psoriatic patients. J Neurolog Sci. 2019;405:84-85.

- Russo PAJ, IIchef R, Cooper AJ. Psychiatric morbidity in psoriasis: a review. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45:155-159.

- Ferreira B, Pio-Abreu JL, Reis JP, Figueiredo A. Analysis of the prevalence of mental disorders in psoriasis: the relevance of psychiatric assessment in dermatology. Psychiat Danub. 2017;29(4):401- 406.

- Esposito M, Saraceno R, Giunta A, et al. An Italian study on psoriasis and depression. Dermatology. 2006;212:123-127.

- Kurd SK, Troxel AB, Crits-Christoph P, Gelfand JM. The risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidality in patients with psoriasis: a population-based cohort study. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(8):891- 895.

- Chi CC, Chen TH, Wang SH, Tung TH. Risk of suicidality in people with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18(5):621-627.

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK, Kirkby S, et al. A psychocutaneous profile of psoriasis patients who are stress reactors. A study of 127 patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1989;11:166-173.

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK, Schork NJ, Ellis CN. Depression modulates pruritus perception: a study of pruritus in psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and chronic idiopathic urticaria. Psychosom Med. 1994;56:36-40.

- Akay A, Pekcanlar A, Bozdag KE, et al. Assessment of depression in subjects with psoriasis vulgaris and lichen planus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:347-352.

- Hrehorów E, Salomon J, Matusiak Ł. Patients with psoriasis feel stigmatized. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:67-72.

- Weiss SC, Kimball AB, Liewehr DJ, et al. Quantifying the harmful effects of psoriasis on health-related quality of life. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:512-518.

- Mufaddel A, Abdelgani AE. Psychiatric comorbidity in patients with psoriasis, vitiligo, acne, eczema and group of patients with miscellaneous dermatological diagnoses. Open J Psychiatry. 2014;4(3):168-175.

- Pietrzak D, Pietrzak A, Grywalska E, et al. Serum concentrations of interleukin 18 and 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 correlate with depression severity in men with psoriasis. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0201589.

- Okereke OI, Singh A. The role of vitamin D in the prevention of late-life depression. J Affect Disord. 2016;198:1-14. 18. Otezla (apremilast) package insert. Thousand Oaks, CA: Amgen Inc; 2021.

- Otezla (apremilast) package insert. Thousand Oaks, CA: Amgen Inc; 2021.

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices. Depression and suicidal behaviors. 2017. www.ismp.org/quarterwatch/depression-and-suicidalbehaviors. Accessed December 22, 2022.

- Colombo D, Caputo A, Finzi A, et al. Evolution of and risk factors for psychological distress in patients with psoriasis: the PSYCHAE study. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2010;23(1):297-306.

- Wu CY, Chang YT, Juan CK, et al. Depression and insomnia in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis taking tumor necrosis factor antagonists. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(22):e3816.

- Vezmar S, Becker A, Bode U, Jaehde U. Biochemical and clinical aspects of methotrexate neurotoxicity. Chemotherapy. 2003;49(1- 2):92-104.

- Balak DMW, Gerdes S, Parodi A, Salgado-Boquete L. Long-term safety of oral systemic therapies for psoriasis: a comprehensive review of the literature. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10(4):589-613.

- Blasco Morente G, Tercedor Sánchez J, Garrido Colmenero C, et al. Pseudotumor cerebri associated with cyclosporine use in severe atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32(2):237-239.

- Okubo Y, Natsume S, Usui K, et al. Low-dose, short-term ciclosporin (Neoral) therapy is effective in improving patients’ quality of life as assessed by Skindex-16 and GHQ-28 in mild to severe psoriasis patients. J Dermatol. 2011;38(5):465-472.

- Hashimoto T, Kawakami T, Tsuruta D, et al. Low-dose cyclosporin improves the health-related quality of life in Japanese psoriasis patients dissatisfied with topical corticosteroid monotherapy. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53(3):202-206.

- Morgan JC, Kurek JA, Davis JL, Sethi KD. Insights into pathophysiology from medication-induced tremor. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y). 2017;7:442.

- Soriatane (acitretin) package insert. Middlesex, UK: Stiefel Laboratories, Inc; 2017.

- Chroni E, Monastirli A, Tsambaos D. Neuromuscular adverse effects associated with systemic retinoid dermatotherapy: monitoring and treatment algorithm for clinicians. Drug Saf. 2010;33(1):25-34.

- Hayes J, Koo J. Depression and acitretin: a true association or a class labeling? J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10(4):409-412.

- Langley RG, Feldman SR, Han C, et al. Ustekinumab significantly improves symptoms of anxiety, depression, and skin-related quality of life in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63(3):457-465.

- Revicki D, Willian MK, Saurat JH, et al. Impact of adalimumab treatment on health-related quality of life and other patient-reported outcomes: results from a 16-week randomized controlled trial in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158(3):549-557.

- Tyring S, Gottlieb A, Papp K, et al. Etanercept and clinical outcomes,fatigue, and depression in psoriasis: double-blind placebo-controlled randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2006;367(9504):29-35.

- Bechtel M, Sanders C, Bechtel A. Neurological complications of biologic therapy in psoriasis: a review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2(11):27-32.

- Al Saieg N, Luzar MJ. Etanercept induced multiple sclerosis and transverse myelitis. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(6):1202-1204.

- Gooderham M, Gavino-Velasco J, Clifford C, et al. A review of psoriasis, therapies, and suicide. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20(4):293- 303.

- Siliq (brodalumab) package insert. Valeant Pharmaceuticals; 2017.

- Stelara (ustekinumab) package insert. Janssen; 2022.

- Gimeno D, Kivimäki M, Brunner EJ, et al. Associations of C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 with cognitive symptoms of depression: 12-year follow-up of the Whitehall II study. Psychol Med. 2009;39(3):413-423.

The content contained in this article is for informational purposes only. The content is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice. Reliance on any information provided in this article is solely at your own risk.