Uterine Fibroids Update for Pharmacists

RELEASE DATE

September 1, 2020

EXPIRATION DATE

September 30, 2022

FACULTY

Kiran Panesar, BPharmS (Hons), MRPharmS, RPh, CPh

Freelance Medical Writer

Consultant Pharmacist

Orlando, Florida

FACULTY DISCLOSURE STATEMENTS

Dr. Panesar has no actual or potential conflicts of interest in relation to this activity.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

Pharmacy

Pharmacy

Postgraduate Healthcare Education, LLC is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education as a provider of continuing pharmacy education.

UAN: 0430-0000-20-099-H01-P

Credits: 2.0 hours (0.20 ceu)

Type of Activity: Knowledge

TARGET AUDIENCE

This accredited activity is targeted to pharmacists. Estimated time to complete this activity is 120 minutes.

Exam processing and other inquiries to:

CE Customer Service: (800) 825-4696 or cecustomerservice@powerpak.com

DISCLAIMER:

Participants have an implied responsibility to use the newly acquired information to enhance patient outcomes and their own professional development. The information presented in this activity is not meant to serve as a guideline for patient management. Any procedures, medications, or other courses of diagnosis or treatment discussed or suggested in this activity should not be used by clinicians without evaluation of their patients’ conditions and possible contraindications or dangers in use, review of any applicable manufacturer’s product information, and comparison with recommendations of other authorities.

GOAL

To review existing pharmacologic therapies available for the management of patients with uterine fibroids, as well as drugs in the pipeline.

OBJECTIVES

After completing this activity, the pharmacist should be able to:

- Review the burden imposed by uterine fibroids.

- Identify risk factors for developing uterine fibroids.

- Review how to counsel patients on the correct use of their medications.

- Recognize new therapies for uterine fibroids when they are available on the market.

- Identify how to engage in a conversation with patients regarding the management of uterine fibroids.

ABSTRACT: Uterine fibroids are the most common benign neoplasms seen in premenopausal women. They place a significant burden on the U.S. economy, costing around $34 billion annually. Race, age, obesity, and family history are some of the main risk factors for the development of uterine fibroids. Older drug therapies for management include nonhormonal nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, tranexamic acids, levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system, and combined oral contraceptives. More recent therapies include the gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonists, and selective progesterone receptor modulators. Surgical procedures, endometrial ablation, and interventional radiology may be required in patients whose fibroids do not respond to drug therapy.

Uterine fibroids, also knowns as leiomyomas, myomas, or fibromyomas, are the most common benign neoplasms found in premenopausal women. Originating in the uterine smooth muscle as microscopic groups of cells, they can grow in and around the uterus wall to more than 20 cm across.

PREVALENCE

Fibroids affect an estimated 11 million women, and the lifetime incidence in the general population is about 70%.1,2 Prevalence varies with age and race/ethnicity. Studies have reported that over 80% of African American women and 70% of Caucasian women develop fibroids by the age of 50 years.3 Since the growth of fibroids depends on estrogens and progesterone, they usually develop during the reproductive years, rarely occurring during puberty, and in most cases, stop growing or shrink at menopause.

ECONOMIC IMPACT

Uterine fibroids are a major public health concern, and they place a significant economic and societal burden on the U.S. economy. It is estimated that 20% to 50% of women experience symptoms and seek gynecologic care.5 Recent data show that fibroids cost the U.S. approximately $34 billion annually.1

RISK FACTORS AND PATHOGENESIS

Race (African descent), age (older than age 40 years), early menarche (age <10 years), family history of uterine fibroids, nulliparity, obesity, polycystic ovary syndrome, hypertension, diabetes, caffeine, and alcohol have all been identified as factors that increase the risk of developing uterine fibroids.6-8 Increased parity, late menarche (>16 years), smoking, and the use of oral contraceptives (particularly progestins), on the other hand, tend to lower this risk.6-8

African American women are not only more likely to develop uterine fibroids compared with white women but are also more likely to be symptomatic at a younger age and have multiple tumors.9 One study showed that the incidence of uterine fibroids in African American women was 60% by age 35 years and >80% by age 50 years, whereas in Caucasian women it was 40% and 70%, respectively.3 Furthermore, African American women have a greater recurrence rate of as high as 59% after 4 to 5 years of surgical management.

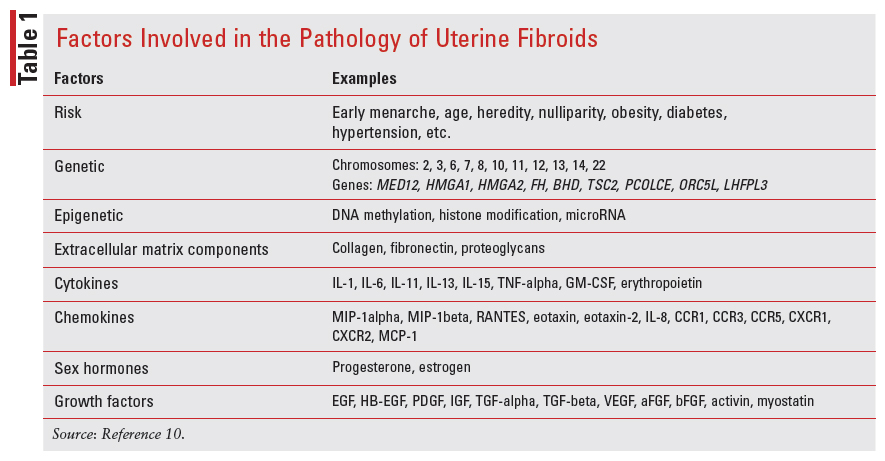

A greater body mass index increases extragonadal production of estrogen and reduces estrogen-binding globulin, thereby increasing the level of estrogen available to fuel the development of fibroids. Obesity is also associated with alterations in metabolic control such as those seen in insulin receptors and insulin-like growth factors, which have been linked to uterine fibroids.9 The underlying pathogenesis of uterine fibroids is still unclear; however, genetic and epigenetic factors, sex steroids, growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, and extracellular matrix components have all been implicated.10 TABLE 1 lists these in more detail.

CLINICAL TYPES

Uterine fibroids consist of both smooth muscle, fibroblast components and a fibrous extracellular matrix.

They are extremely heterogenous in their size, number, and location and can be divided into three types depending upon the growth site: intramural (growing inside the uterine wall), subserosal (projecting outside the uterus), and submucosal (growing inside the uterus, under the endometrium—partially in the cavity and partially in the wall of the uterus). The size, number, and location of the tumors affect the presenting symptoms and influence the management options. Intramural fibroids are usually not problematic unless they become quite large, in which case they can distort the uterine cavity and cause fertility issues. Subserosal fibroids can grow quite large and often put pressure on the surrounding organs. Submucosal fibroids are very rare and are only seen in about 5% of cases. These fibroids sometimes grow large enough to protrude through the cervix.

SYMPTOMS AND COMPLICATIONS

The most common presenting symptoms are abnormal uterine bleeding, dysmenorrhea, and pelvic pain. Abnormal uterine bleeding has been observed in 64% of women with fibroids.11

Heavy or prolonged menstrual bleeding can lead to iron-deficiency anemia.12 The fibroid can place pressure on neighboring organs, leading to a host of symptoms depending upon its size and location. Symptoms may include pelvic and abdominal pain, heaviness, bloating, and cramps. Pressure on the bladder may result in urinary frequency or stress incontinence. Pressure on the intestines may lead to constipation or painful bowel movements. Fertility problems and complications during pregnancy, labor, and delivery, as well as following birth, have all been noted in women with fibroids.

DIAGNOSIS

Ultrasonography is the preferred initial diagnostic tool and is between 90% and 99% sensitive at detecting uterine fibroids, although it may miss subserosal or smaller fibroids.13,14 Other techniques include hysteroscopy, laparoscopy, biopsy, and magnetic resonance imaging.

MANAGEMENT

The aim of treatment is fourfold: alleviating symptoms, shrinking the fibroids, maintaining fertility, and avoiding harm.15 Both pharmacologic therapy and medical procedures are available for the management of fibroids.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists proposes some alternatives to hysterectomy in the management of fibroids. These guidelines were first published in 2008 and reaffirmed in 2019.12 In addition to the size and location of the tumors, it is important to consider a patient’s symptoms, age, desire for future fertility, proximity to menopause, access to treatment, and the physician’s experience when selecting a management option.9,15 Women with mild symptoms or those nearing menopause may choose not to be treated, whereas those with large fibroids or those in whom fertility is affected may consider treatment. Abnormal uterine bleeding and heavy menstrual bleeding can often be managed with pharmacologic therapy such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), progestin, combined oral contraceptives, a levonorgestrel-releasing IUD or tranexamic acid.3 Surgical intervention, including endometrial ablation or hysterectomy, may be required for patients with anatomical lesions, causing abnormal uterine bleeding.

Nonhormonal Pharmacologic Treatment

NSAIDs: NSAIDs include mefenamic acid, naproxen, ibuprofen, flurbiprofen, diclofenac, indomethacin, and acetylsalicylic acid. They inhibit cyclooxygenase and, therefore, reduce the production of prostaglandins, which are elevated in excessive menstrual bleeding. As such, NSAIDs reduce both pain and blood loss in women but do not have any effect on the size of the fibroid. They are useful in women with dysmenorrhea who do not desire contraception. A Cochrane Review concluded that NSAIDs are more effective than placebo but are less effective than tranexamic acid, danazol, or the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) at reducing heavy menstrual bleeding.16 The review did not find any difference between the NSAIDs naproxen and mefenamic acid at reducing heavy menstrual bleeding.16

Pharmacists should advise patients to take the recommended dose from the first day of menstruation, regularly as needed, and with or after food to avoid gastrointestinal (GI) disturbance. The use of NSAIDs is contraindicated in peptic ulceration.

Tranexamic Acid: Tranexamic acid is a synthetic lysine derivative that prevents the degradation of fibrin by competitively blocking lysine-binding sites on plasminogen. In this way, it promotes clotting and therefore reduces menstrual blood flow. It is more effective than placebo and NSAIDs at reducing blood flow, but its efficacy in controlling bleeding related to uterine fibroids is not well established.3,17

Tranexamic acid is licensed by the FDA for the management of abnormal uterine bleeding or heavy menstrual bleeding secondary to ovulatory disorders but not for uterine leiomyoma. If used in the management of uterine fibroids, the recommended dose is 1,300 mg orally or 10 mg/kg (maximum 600 mg/dose) intravenously three times daily for up to 5 days during menstruation. Tranexamic acid can cause fibroid necrosis and infarction, resulting in pain and providing a site for infection. Tranexamic acid has been associated with deep vein thrombosis and is therefore contraindicated in women who have or are at risk of developing thromboembolic disease.

Despite all of these factors, tranexamic acid is often used in the symptomatic control of uterine fibroid– related bleeding episodes. The first dose should be taken when menstrual bleeding has started. GI discomfort is the most common side effect of tranexamic acid, and patients should be advised to take it with or after meals.

Hormonal Pharmacologic Treatment

Combined Oral Contraceptives (Estrogen and Progestin Combinations): Since gonadal hormones are required for the initiation and growth of uterine fibroids, the use of combined oral contraceptives (COCs) was not recommended in women with uterine fibroids. However, one trial demonstrated that risk of uterine fibroid– associated morbidity is decreased by 17% in women taking COCs for 5 years or longer. Furthermore, an observational study comparing COCs to placebo noted a reduction of more than 2 days in menstrual bleeding and improvement in hematocrit without changes in uterine volume. Even though the evidence is not clear, COCs are used in women with uterine fibroids.3,11

Progestins: Oral progestins may all work to reduce blood loss by inhibiting endometrial proliferation, leading to a thinner lining with less material to be shed during progestin withdrawal.

The LNG- IUS continuously releases levonorgestrel to repress estrogenic-stimulated growth. This results in the thinning of the endometrium and, therefore, a contraceptive effect.18,19 Since the device inhibits ovulation in some women, it will temporarily affect fertility. The LNG-IUS has been shown to reduce the duration and amount of menstrual bleeding with minimal uptake of levonorgestrel into the systemic circulation.12 Mirena releases 20 µg/day of levonorgestrel for the first few years, decreasing to about 10 µg/day after about 3 years. The device can be expelled spontaneously in a small number of women (~10%), and some women (~5%) may experience irregular bleeding and persisting menorrhagia or pain.11 LNG-IUS has been associated with acne, tenderness, weight gain, bloating, and ovarian cysts.

Studies have however demonstrated mixed results with progestin only therapy reducing the leiomyomata volume in some, and increasing the volume in others.3 There are no progestins that have FDA approval for the management of uterine fibroids.

Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonists: The pulsatile release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus stimulates the pituitary to release follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), which in turn stimulate the synthesis and secretion of the ovarian hormones 17 beta-estradiol and progesterone, respectively.

Initial administration of GnRH agonists causes a “flare-up effect,” stimulating the secretion of LH and FSH and an initial rise in estrogen levels. Repeated administration causes downregulation of GnRH receptors, leading to a reduction in gonadotropin secretion and a hypoestrogenic state. Since uterine fibroids are estrogen dependent, the resultant effect is a decrease in uterine and fibroid volume. GnRH agonists improve menorrhagia and, in many cases, lead to amenorrhea. The GnRH agonist leuprolide acetate has been shown to temporarily reduce uterine size and fibroid-related symptoms.20 The fibroid can increase up to its original size within 3 months upon discontinuation of therapy.11

Often, GnRH agonists are used preoperatively to decrease fibroid volume and allow for less invasive surgical techniques. It has been shown that the use of GnRH agonists for 3 to 4 months preoperatively reduces uterine and fibroid volume and increases the likelihood of having a vaginal rather than abdominal hysterectomy.6,21 Furthermore, preoperative iron deficiency anemia is corrected and intraoperative blood loss is reduced. The preoperative use of GnRH agonists can, however, cause complications such as hemorrhage from regeneration, increased tumor hyalinization, and the reduction of small fibroids into surgically indetectable ones.22,23

Patients taking GnRH agonists should be advised to have their bone mineral density checked regularly because prolonged use is associated with loss of bone mass that may not reverse upon discontinuation of medication. Other side effects include menopause-like symptoms of estrogen deficiency, such as hot flashes, insomnia, increased sweating, muscle stiffness, vaginal atrophy, headache, and mood disorders.11 The use of GnRH analogues is limited by their side effects. Addback therapy is a strategy in which other medications are added to reduce these side effects.11

Lupron Depot (containing leuprolide acetate) is a GnRH agonist licensed by the FDA for the treatment of uterine fibroids.24 It is administered intramuscularly and should be given along with iron supplementation to improve anemia from fibroids. The recommended dose for Lupron ddepot is 3.75 mg monthly for up to 3 months or 11.25 mg as a single dose. Its use is contraindicated in women with undiagnosed vaginal bleeding. No drug-drug interaction studies have been conducted with Lupron Depot.24 Lupron is not indicated for use in pregnancy, pediatric populations, or postmenopausal women. The GnRH agonists goserelin and nafarelin are not licensed for the management of uterine fibroids.

A Cochrane Review conducted to assess the effec tiveness of add-back therapy in women taking GnRH analogues concluded that there was low-moderate evidence that tibolone, raloxifene, estriol, and iprifla vone preserve bone density and that medoxyproges terone and tibolone reduce vasomotor symptoms. The review also noted that the add-back therapies medroxy progesterone, tibolone, and conjugated estrogens were associated with larger uterine volumes as an adverse effect.6 A systematic review was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of add-back therapy, com paring the combination of GnRH analogues with pro gesterone, raloxifene, tibolone, or estrogen-progesto gen to a GnRH analogue alone. The authors concluded that the addition of progestogen, tibolone, or raloxi fene to GnRH analogues can prevent menopausal symptoms and bone loss, but the combination does not seem to increase or decrease efficacy.21

GnRH Antagonists: GnRH antagonists bind to the GnRH receptors in the pituitary glands, suppressing the production of LH and FSH and decreasing the serum concentration of the ovarian sex hormones faster than the GnRH agonists. A number of GnRH antagonists have been synthesized; however, only a few are being further developed.

Elagolix is an oral GnRH antagonist that has been shown to reduce fibroid-associated bleeding.25 The FDA recently approved Oriahnn for the management of heavy menstrual bleeding associated with uterine fibroids. Oriahnn is a combination of 300-mg elagolix and the endogenous hormones estradiol, 1 mg, and norethindrone acetate, 0.5 mg, estrogen, and progestin as add-back therapy.26 The recommended dose of Oriahnn is one capsule (elagolix 300 mg, estradiol 1 mg, norethindrone acetate 0.5 mg) every morning and one capsule (elagolix 300 mg) every night for up to 24 months. Oriahnn may be associated with thromboembolic disorders, suicidal ideation, and mood disorders. Since Oriahnn alters the menstrual bleeding pattern, pharmacists should advise women taking Oriahnn to use nonhormonal contraception during and up to 1 week after discontinuing therapy.26 Pregnancy should be excluded before therapy is initiated. If pregnancy is suspected, a pregnancy test should be carried out; if pregnancy is confirmed, Oriahnn should be discontinued.26

Relugolix is currently undergoing phase III clinical trials for use in the management of heavy menstrual bleeding associated with uterine fibroids. The LIBERTY 1 and 2 studies assessed the combination of 40-mg relugolix + 1-mg estradiol and 0.5-mg norethindrone in women with uterine fibroids. It has been shown that Relugolix-CT significantly reduces menstrual blood loss in women with heavy bleeding associated with uterine fibroids. This combination is currently under review by the FDA.27 Relugolix combination therapy seems to preserve bone mass over 24 weeks when compared with relugolix monotherapy and reduces uterine fibroid–associated pain when compared with placebo.28,29 In comparison with the GnRH agonist leuprorelin, relugolix was associated with an earlier reduction in the amount of uterine bleeding and a faster recovery of menses after discontinuation.29

Linzagolix is an investigational GnRH receptor antagonist that reduces heavy menstrual bleeding caused by uterine fibroids while mitigating bone mineral density loss.30,31 The phase III PRIMROSE 2 trial conducted by ObsEva evaluated the safety and efficacy of 100-mg and 200-mg once-daily administration of linzagolix with and without hormonal add-back therapy. It was found that at both doses, linzagolix achieved significant rates of amenorrhea, reduction in pain, and improvement in quality of life as well an improvement in hemoglobin levels, a reduction in the number of days of bleeding, and reduction in uterine volume. The 200mg dose also achieved a significant reduction in fibroid volume. The most common adverse effects noted were headache, hot flushes, and anemia. Linzagolix is not yet FDA approved.

Cetrorelix acetate is an injectable GnRH that has shown effectiveness in reducing fibroid volume and uterine volume when used at a dose of 10 mg on Days 1, 8, 15, and 22.11 It directly inhibits the production of extracellular matrix by regulating type 1 collagen, fibronectin, and matrix proteoglycan production.3 Rapid reduction in fibroid volume is also noted with the GnRH antagonist ganirelix at a daily dose of 2 mg administered subcutaneously for 3 weeks.3 In this trial, ganirelix was associated with minor side effects, including hot flushes and headache. Since both cetrorelix and ganirelix are only available in injectable formulations that need to be administered every 1 to 4 days, their usefulness in the management of uterine fibroids is limited. These drugs have not been developed and licensed for the management of uterine fibroids.32

Selective Progesterone Receptor Modulators: Progesterone is central to the regulation of normal uterine function and is also implicated in the development and growth of uterine fibroids. Selective progesterone receptor modulators (SPRMs) are structurally similar to progesterone and mifepristone. They demonstrate tissue-specific agonist or antagonist actions by conforming to the receptor once they are taken up. Depending upon the type of resultant change and the availability of coregulators, they have an agonist or antagonistic effect. SPRMs act directly on the cells of the fibroid, inhibiting cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis and reducing its volume.32 Additionally, they act directly on the pituitary gland (unlike GnRH agonists) and the endometrium to control bleeding and amenorrhea.

Ulipristal acetate is an oral SPRM with a partial progesterone antagonist effect that can be used to treat moderate to severe symptoms of uterine fibroids and has shown positive results when assessed for quality of life and symptom severity.33 However, ulipristal acetate has been known to cause serious liver injury in rare cases and is therefore not FDA approved. In Europe, the European Medicines Agency has temporarily sus pended the license for ulipristal acetate for uterine fibroids as it further investigates the risk of liver injury.34 Ulipristal acetate is licensed for use as an emer gency contraceptive, and there is no apparent risk of liver injury with this indication.

Vilaprisan is a new investigational orally available SPRM with antiproliferative activity against uterine fibroids. Early trials have shown that vilaprisan can reduce amenorrhea in patients with uterine fibroids, decreasing heavy menstrual bleeding and uterine fibroid volume. There were no safety concerns after 2 mg over 12 weeks treatment.35 Currently, all trials have been halted, possibly due to the safety concerns with ulipristal.36

Telapristone (also known as CDB-4124) and asoprisnil (also known as J867) are both SPRMs that reduce fibroid and uterine volume and improve fibroidrelated symptoms without serious complications. These molecules are up and coming potential molecules to study.6

Antiestrogens: Drugs with antiestrogenic properties such as tamoxifen, raloxifene, and fulvestrant have not yielded any positive results in trials examining their effectiveness in the management of patients with uterine fibroids.11,37

MEDICAL PROCEDURES

Surgical procedures, endometrial ablation, and interventional radiology are often used in the management of uterine fibroids. Different surgical techniques have been employed, including total abdominal hysterectomy or myomectomy.

Uterine fibroids are the leading indication of hysterectomy in the U.S., and this procedure is useful in women aged 40 to 50 years or in those who do not wish to conceive.3 Vaginal hysterectomy is the least costly option and is less invasive than a total abdominal hysterectomy, allowing for the removal of even larger fibroids.38 Supracervical hysterectomy is conducted in more complicated cases. Laparoscopic techniques have been successfully used more recently to reduce the impact of hysterectomy.6

Uterine artery embolization (UAE) is a safe and minimally invasive technique that has a lower rate of complications and similar satisfaction to hysterectomy. However, there is an increased probability of the need for another surgical procedure to be done in 2 to 5 years. It is therefore a useful option for women who wish to preserve their uterus. UAE is associated with pregnancy complications and an increased risk of cesarean delivery. It is important that women are advised of these risks before the procedure.

Endometrial ablation destroys the tissue using different types of concentrated energy such as radiofrequency, ultrasound, thermal balloon microwave, or laser ablation. Magnetic resonance imaging–guided techniques reduce the need for surgical procedures to guide the energy source.

ROLE OF THE PHARMACIST

In addition to dispensing and counseling on the medications a patient may be taking, pharmacists can ensure adherence to therapy for maximum effectiveness. Pharmacists can also suggest other ways in which patients can relieve pain caused by uterine fibroids. In mild cases, the application of local heat using a hot water bottle or a heating pad, the use of a TENS machine, or various exercises can be discussed with patients. For overweight patients, pharmacists can suggest ways to reducing excess weight, which might be leading to worse symp toms. Pharmacists can also assist patients in setting up a symptom diary to record pain, cycle timings, and dura tion and rate of bleeding through the number of sanitary pads or tampons used.

With newer pharmacologic therapies expected on the market in the near future, knowledgeable phar macists will be a in a strong position to ensure that their patients’s fibroids are optimally managed.

The content contained in this article is for informational purposes only. The content is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice. Reliance on any information provided in this article is solely at your own risk.

REFERENCES

- Florence AM, Fatehi M. Leiomyoma. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- Styer AK, Rueda BR. The epidemiology and genetics of uterine leiomy oma. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;34:3-12.

- Lewis TD, Malik M, Britten J, et al. A comprehensive review of the pharmacologic management of uterine leiomyoma. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:2414609.

- Dragomir AD, Schroeder JC, Connolly A, et al. Potential risk factors associated with subtypes of uterine leiomyomata. Reprod Sci. 2010;17(11):1029-1035.

- Vilos GA, Allaire C, Laberge PY, Leyland N. The management of uter ine leiomyomas. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015;37(2):157-178.

- Farris M, Bastianelli C, Rosato E, et al. Uterine fibroids: an update on current and emerging medical treatment options. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2019;15:157-178.

- Ryan GL, Syrop CH, Van Voorhis BJ. Role, epidemiology, and natural history of benign uterine mass lesions. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;48(2):312-324.

- Chiaffarino F, Parazzini F, La Vecchia C, et al. Use of oral contracep tives and uterine fibroids: results from a case-control study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106(8):857-860.

- Bass J, Benn C. Fibroids: advice and treatment options. Pharma Jour. 2014;292(7802/3):338.

- Islam MS, Protic O, Giannubilo SR, et al. Uterine leiomyoma: avail able medical treatments and new possible therapeutic options. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(3):921-934.

- Moroni R, Vieira C, Ferriani R, et al. Pharmacological treatment of uterine fibroids. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2014;4(Suppl 3):S185-S192.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin. Alternatives to hysterectomy in the management of leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 Pt 1):387-400.

- Dueholm M, Lundorf E, Hansen ES, et al. Accuracy of magnetic reso nance imaging and transvaginal ultrasonography in the diagnosis, map ping, and measurement of uterine myomas. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(3):409-415.

- Cicinelli E, Romano F, Anastasio PS, et al. Transabdominal sonohys terography, transvaginal sonography, and hysteroscopy in the evaluation of submucous myomas. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85(1):4247.

- De La Cruz MS, Buchanan EM. Uterine fibroids: diagnosis and treat ment. Am Fam Physician. 2017;95(2):100-107.

- Bofill Rodriguez M, Lethaby A, Farquhar C. Non-steroidal anti inflammatory drugs for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;9(9):CD000400.

- Naoulou B, Tsai MC. Efficacy of tranexamic acid in the treatment of idiopathic and non-functional heavy menstrual bleeding: a systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91(5):529-537.

- Mirena [package insert]. Wayne, NJ: Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuti cals. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/021225s019lbl. pdf. Accessed June 15, 2020.

- Grigorieva V, Chen-Mok M, Tarasova M, Mikhailov A. Use of a levo norgestrel-releasing intrauterine system to treat bleeding related to uterine leiomyomas. Fertil Steril. 2003;79(5):1194-1198.

- Friedman AJ, Hoffman DI, Comite F, et al. Treatment of leiomyomata uteri with leuprolide acetate depot: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. The Leuprolide Study Group. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77(5):720-725.

- Lethaby A, Vollenhoven B. Fibroids (uterine myomatosis, leiomyomas). BMJ Clin Evid. 2011:0814.

- De Falco M, Staibano S, Mascolo M, et al. Leiomyoma pseudocapsule after pre-surgical treatment with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists: relationship between clinical features and immunohistochemical changes. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;144(1):44-47.

- Cohen D, Mazur MT, Jozefczyk MA, Badawy SZ. Hyalinization and cellular changes in uterine leiomyomata after gonadotropin releasing hor mone agonist therapy. J Reprod Med. 1994;39(5):377-380.

- Lupron Depot [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie. www. lupron.com/prescribing-information.aspx. Accessed June 18, 2020.

- Schlaff WD, Ackerman RT, Al-Hendy A, et al. Elagolix for heavy men strual bleeding in women with uterine fibroids. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(4):328-340.

- Oriahnn [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie. www.rxabbvie. com/pdf/Oriahnn_pi.pdf. Accessed June 18, 2020.

- Myovant Sciences. Myovant Sciences submits New Drug Applica tion (NDA) to the FDA for Once-Daily Relugolix Combination Tab let for the treatment of women with uterine fibroids. June 1, 2020. www.ds-pharma.com/ir/news/pdf/ene20200602.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2020.

- McClung MR, Santora AC, Al-Hendy A, et al. Bone mineral den sity assessment with Relugolix combination therapy: results from the phase 3 LIBERTY Program [OP04-2D]. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:6S.

- Osuga Y, Enya K, Kudou K, et al. Oral gonadotropin-releasing hor mone antagonist Relugolix compared with leuprorelin injections for uter ine leiomyomas: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(3):423-433.

- ObsEva. Linzagolix. www.obseva.com/linzagolix/. Accessed June 21, 2020.

- Donnez O, Donnez J. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist (linzagolix): a new therapy for uterine adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2020;S0015-0282(20):30345-30349.

- Rabe T, Saenger N, Ebert AD, et al. Selective progesterone receptor modulators for the medical treatment of uterine fibroids with a focus on ulipristal acetate [correction published in Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:6124628]. Biomed Res Int. 2018:2018;1374821.

- Lukes AS, Soper D, Harrington A, et al. Health-related quality of life with ulipristal acetate for treatment of uterine leiomyomas: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(5):869-878.

- European Medicines Agency. Suspension of ulipristal acetate for uter ine fibroids during ongoing EMA review of liver injury risk. March 13, 2020. www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/suspension-ulipristal-acetate-uterine fibroids-during-ongoing-ema-review-liver-injury-risk. Accessed June 23, 2020.

- Gemzell-Danielsson K, Heikinheimo O, Zatik J, et al. Efficacy and safety of vilaprisan in women with uterine fibroids: data from the phase 2b randomized controlled trial ASTEROID 2. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;252:7-14.

- Ciebiera M, Vitale SG, Ferrero S, et al. Vilaprisan, a new selective pro gesterone receptor modulator in uterine fibroid pharmacotherapy—will it really be a breakthrough? Curr Pharm Des. 2020;26(3):300-309.

- Donnez J, Hervais Vivancos B, Kudela M, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trial comparing fulvestrant with goserelin in premenopausal patients with uterine fibroids awaiting hysterectomy. Fertil Steril. 2003;79(6):1380-1389.

- Mas A, Tarazona M, Dasí Carrasco J, et al. Updated approaches for management of uterine fibroids. Int J Womens Health. 2017;9: 607-617.